Voter Disenfranchisement in Virginia

History of Voter Suppression & Felony Disenfranchisement

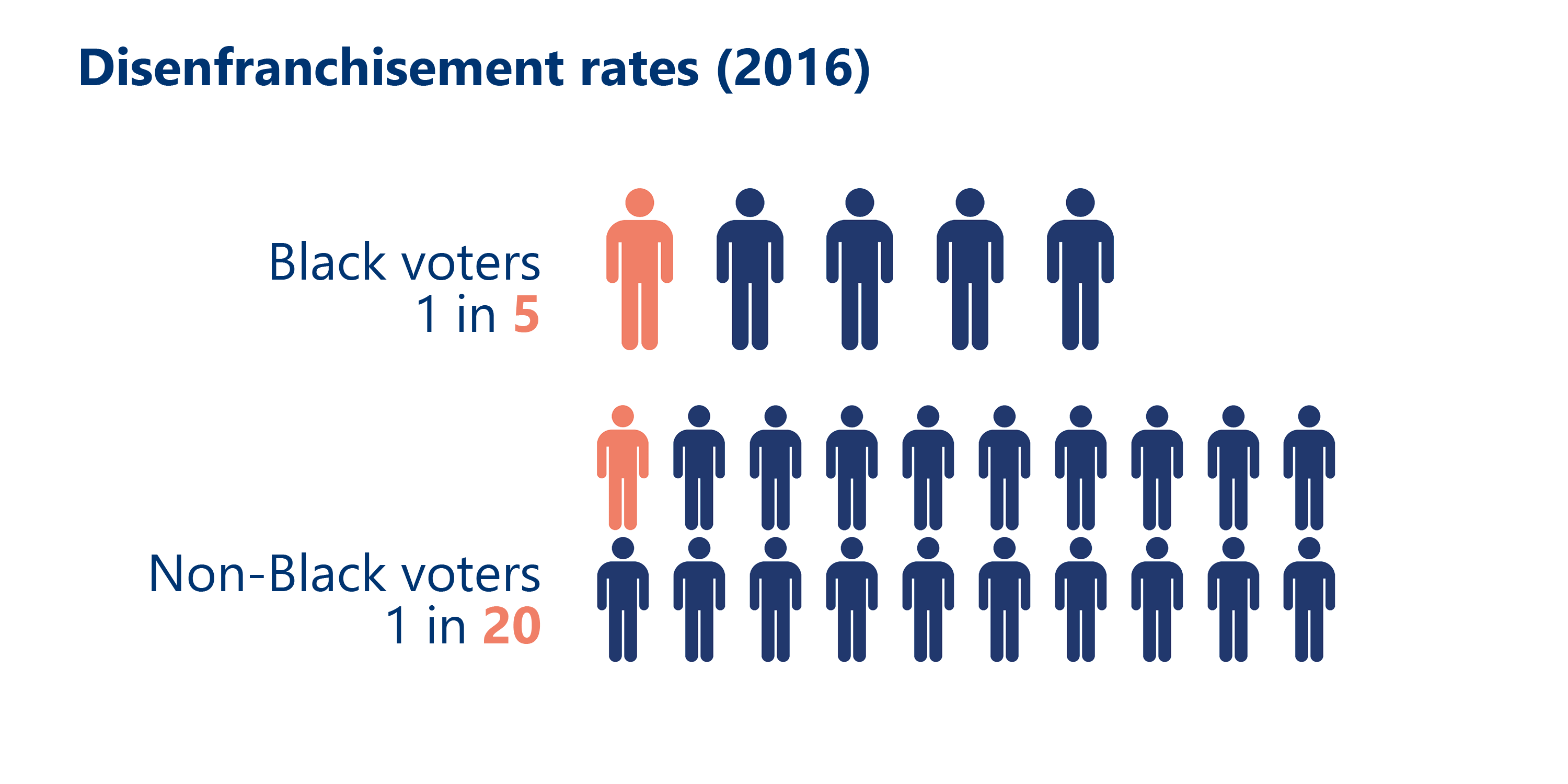

In 2016, Black voter turnout dropped by 7% nationally, birthing many theories as to why African American voters just “didn’t show up” at such a critical time. However, the story is not that simple. The decline in African American turnout was not a refusal by the Black voter to participate but a willful and successful attempt – 150 years in the making – to block them from the ballot box. Many policy decisions throughout history have blocked millions of Black voters from the ballot box, but no law has had greater long- term impact than felony disenfranchisement. At last count, nearly 350,000 Virginians cannot vote due to a felony conviction, the majority of whom are Black and Brown – a restriction put in place centuries ago but exploited after the abolition of slavery to control and restrict Black voices.

1792

States first began establishing criminal disenfranchisement in the late 1700s but with very narrow criteria. In 1792, when Kentucky first inserted a clause into their constitution adding “bribery, perjury, forgery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors” to the list of disqualifying factors that would cost you your right to vote, Black people amassing political or social power was not a concern or a threat. By the end of the Civil War however, states were already incarcerating Black people at a higher rate than whites. Criminal disenfranchisement was already ripe for exploration.

1865

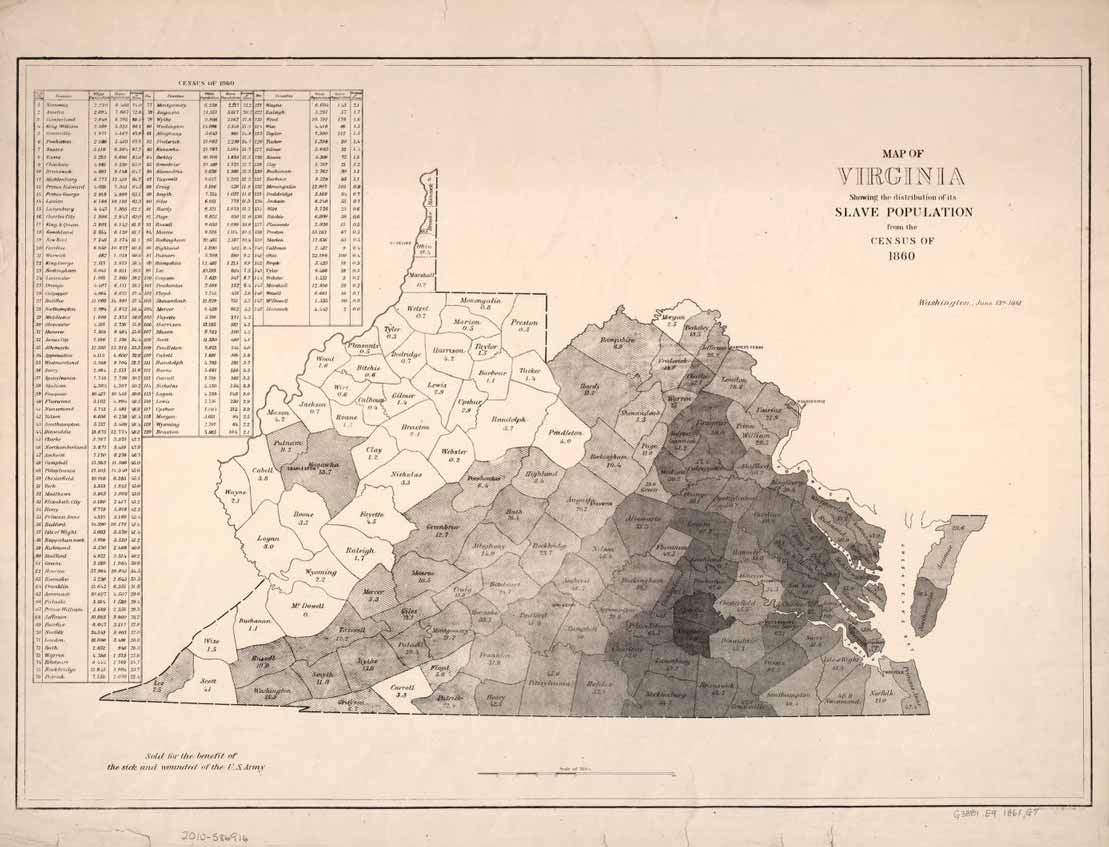

The 13th Amendment passed in 1865 and formally abolished slavery on paper. Suddenly, the now freed but formerly enslaved Black population of Virginia outnumbered whites in 39 of the 148 counties and made up at least 20% of the population in 78 of the counties. For the first time, Black people were given American citizenship, and Black men were given the ability to vote and hold public office. Over 2,000 Black men were elected in the immediate years following the ratification of the 13th , 14th , and 15th amendments. The notable exception of the 13th amendment, however, was that you could still enslave people legally if they were convicted of a crime and once convicted of a crime you could be disenfranchised. It was a powerful one-two punch that was quickly exploited by white leaders to retain power.

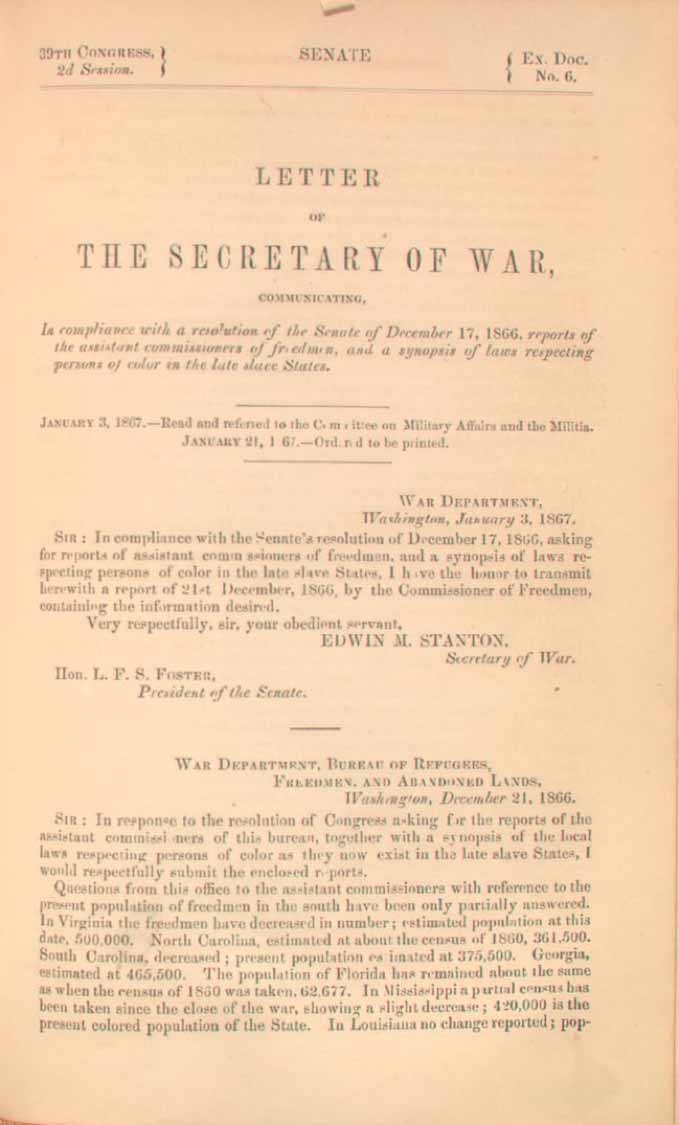

1866

As the 13th Amendment to the Constitution prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, but explicitly exempted those convicted of a crime, states across the South quickly passed Black Codes – new laws that explicitly applied only to Black people and subjected them to criminal prosecution for offenses like loitering, breaking curfew, vagrancy, and not carrying proof of employment.

Excerpt: Be it enacted by the general assembly, That the overseers of the poor, or other officers having charge of the poor, or the special county police, or the police of any corporation, or any one or more of such persons, shall be and are hereby empowered and required, upon discovering any vagrant or vagrants within their respective counties or corporations, to make information thereof to any justice of the peace of their county or corporation, and to require a warrant for apprehending such vagrant or vagrants, to be brought be before him or some other justice...

1870

Without a source of free labor, and with a Black population that was quickly growing its social and political power, the South came up with inventive ways to take advantage of the loopholes in the 13th amendment and find a quick replacement for enslaved labor. The practice of “convict leasing” began shortly after the Civil War, where incarcerated people were leased out to work for private individuals. Minor crimes and fabricated charges came with fines and fees that forced mostly Black men into labor for an employer to settle their debt. Often the paperwork and debt records were lost, and the men were unable to prove their debt had been paid. The results were clear, In 1850, 2% of people who were incarcerated in Alabama were non-white but by 1870, the non-white prison population grew to 74% and an astonishing 90% of the “leased” convict laborers were Black.

1868 - 1870

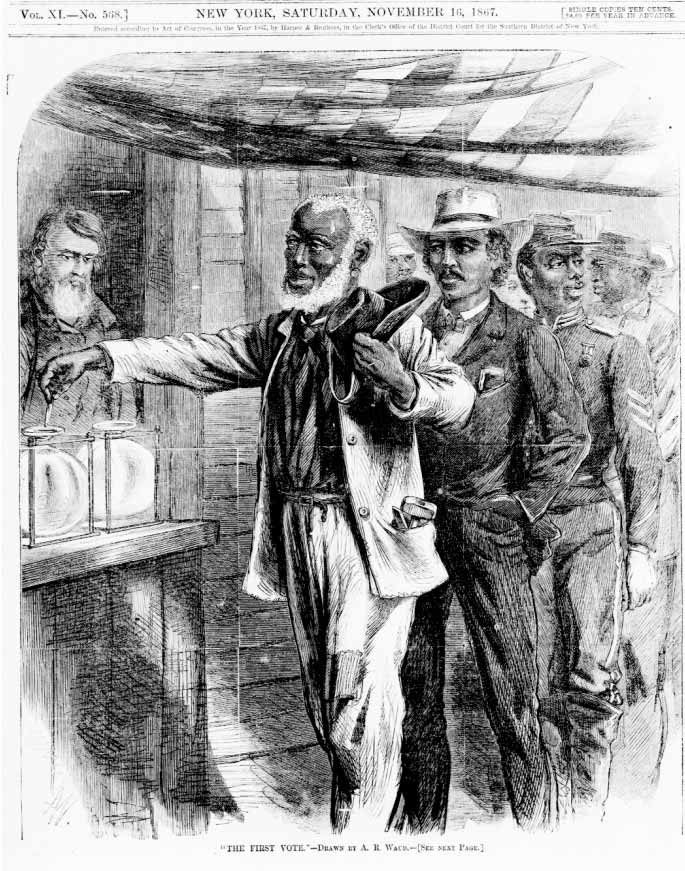

After the end of the Civil War, US Congress forced former confederate states to write new state constitutions. In an effort to limit southern states from exploiting the criminal disenfranchisement loophole in the 15th amendment, Congress mandated a limitation on what kind of crimes you could disfranchise people for: felonies. In Virginia, the commanding Army general ordered that Black men be allowed to vote in the 1867 election of delegates that would go on to write that constitution. Nearly 90% of the 105,832 formerly enslaved African Americans of Virginia cast a ballot. That year, Virginia elected 24 African Americans to the 1868 Constitutional Convention.

1868 - 1870

In Virginia’s first integrated election, ballots were still counted separately in different ballot boxes for whites and “coloreds.” In 1870, the 15th Amendment was ratified to extend the right to vote to Black people stating that the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

1868 - 1870

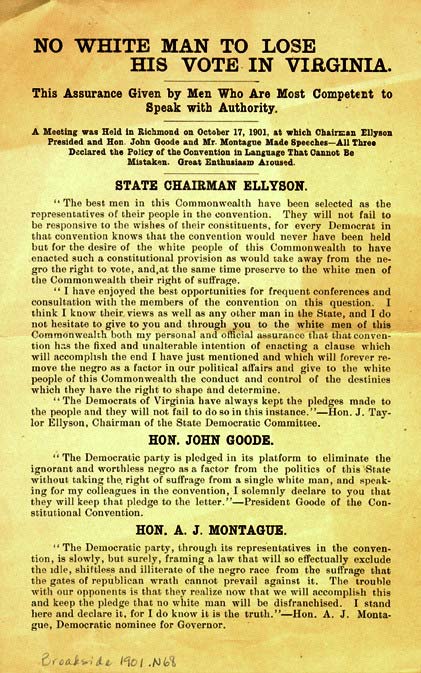

In the first constitutional convention following the Civil War, changes were made to Virginia’s constitution that would open the right to vote to every man age “21 and over...regardless of race.” The new constitution also outlined a series of ways that Blacks would be integrated into Virginia society. Among those rights was the ability to testify in court and attend public school. This racist broadside was published by opponents of the reformist constitution to incite fear into white Virginia voters by conjuring images of what giving this kind of political and social power to Black people would mean. Ultimately the new Virginia constitution was ratified in 1869 and the new General Assembly included 27 African Americans.

1870 - 1901

Over the next three decades, fearful of “Black rule,” the 11 former confederate states schemed to come up with ways to disfranchise Black voters and reclaim white political supremacy. The challenge was how to do it without violating the 15th Amendment of the US Constitution. Each effort followed a familiar pattern - identify a racially neutral trait or circumstance (income status, conviction of crimes, illiteracy) and determine voting eligibility based on that trait.

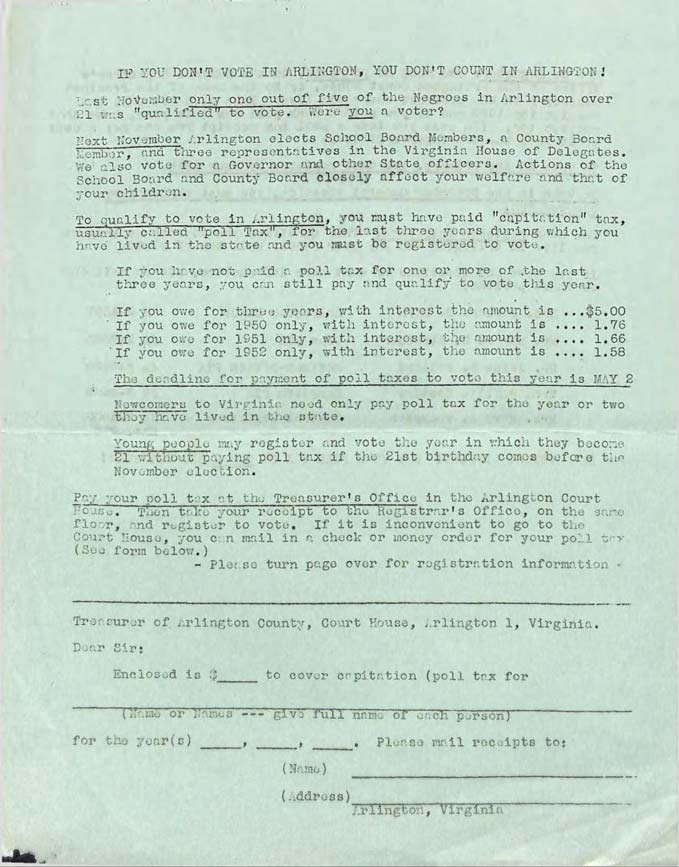

Across the South, laws were passed to intentionally block Black people’s access to the ballot. Blacks were increasingly convicted of crimes at higher rates, barring their access to the ballot through minor criminal disenfranchisement. During this time, Virginia passed a blatantly racist law targeting the low socioeconomic status of Black Virginians requiring payment of a “poll tax” six months in advance in order to vote. Notice that the image below is from the 1950s. While the poll tax was briefly repealed by the General Assembly after its initial passage in 1876, it was reinstated in 1902 and continued in Virginia until it was proven unconstitutional in the late 1960s.

1876

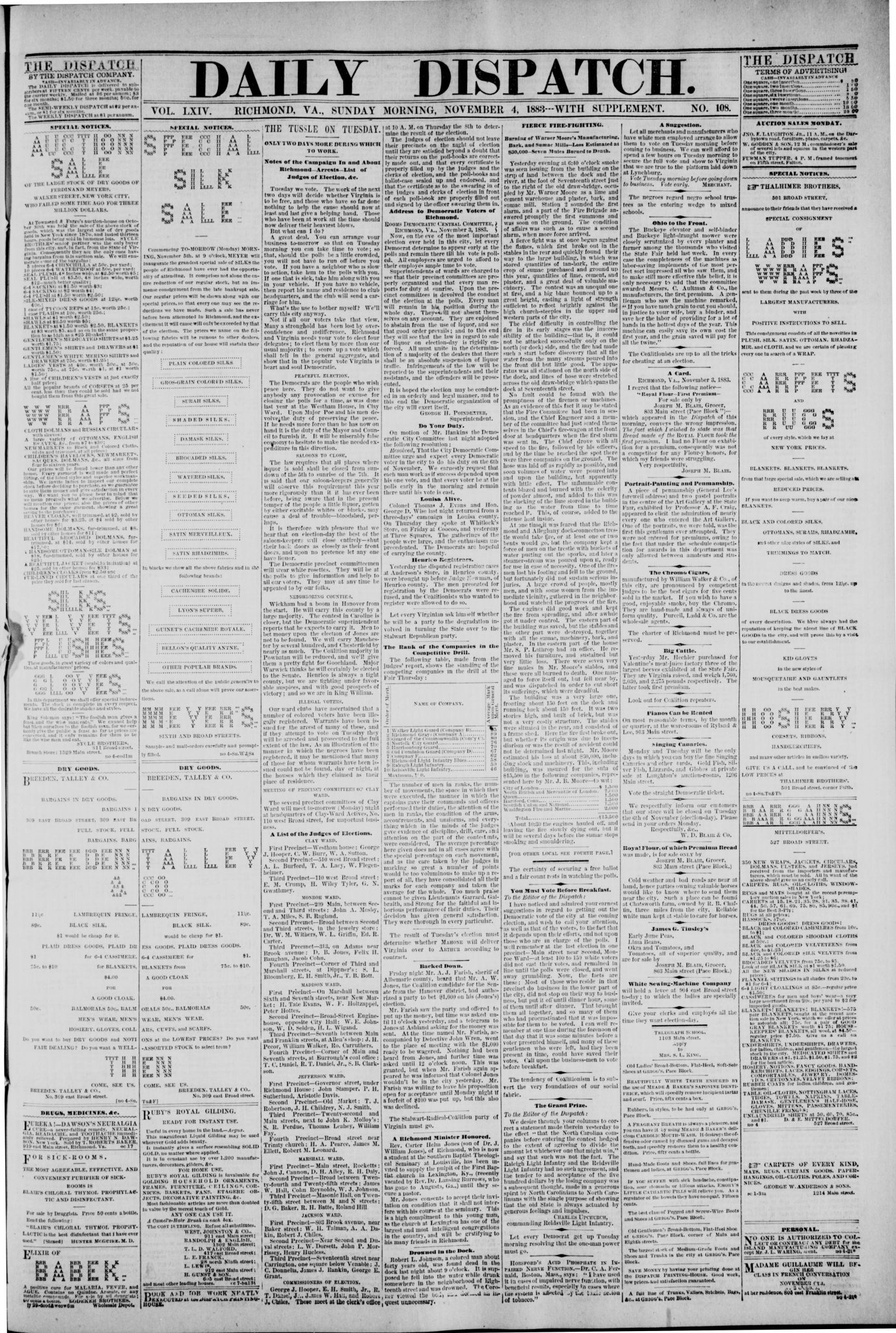

In 1876, Virginia expanded the list of crimes that would cost you your right to vote to include petty larceny, a crime that constituted most felony convictions for enslaved people in the 1800s. The next year, the legislature passed a law that required lists of voters convicted of any of the disenfranchising crimes be delivered to county registrars. A Richmond-based newspaper at the time wrote, “We publish elsewhere a list of negroes convicted of petit larceny,” advising that “Democratic challengers should examine it carefully.

1880

By 1880, at least 13 states — more than a third of the country’s 38 states at the time — had passed broad felony disenfranchisement laws in their constitution or legislature. 16 By 1900, a new constitutional convention was called so Virginia could join the ranks. This constitution had a very explicit purpose: to “purify” and block Black people from the ballot. In the words of Lynchburg Delegate Carter Glass, they would “discriminate to the very extremity...permissible...under the Federal Constitution, with a view to the elimination of every negro voter who can be gotten rid of, legally, without materially impairing the numerical strength of the white electorate.

1901-1902

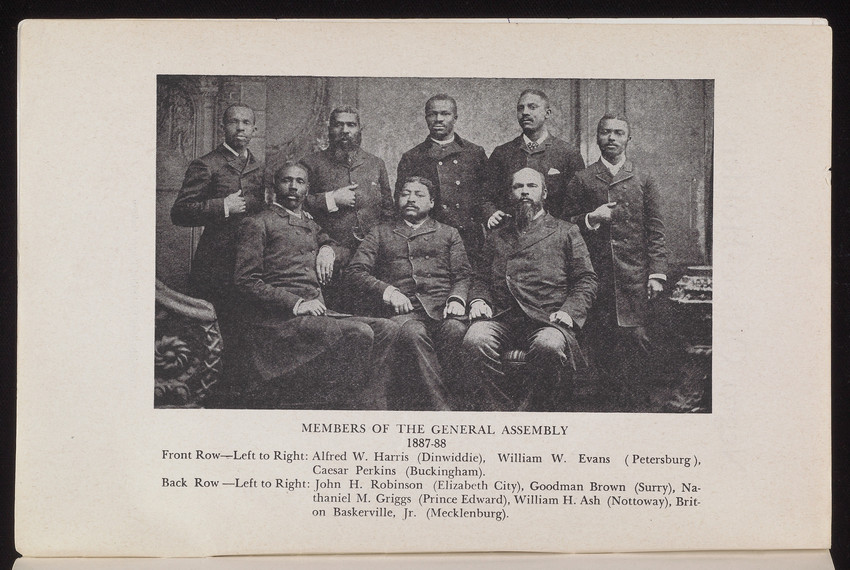

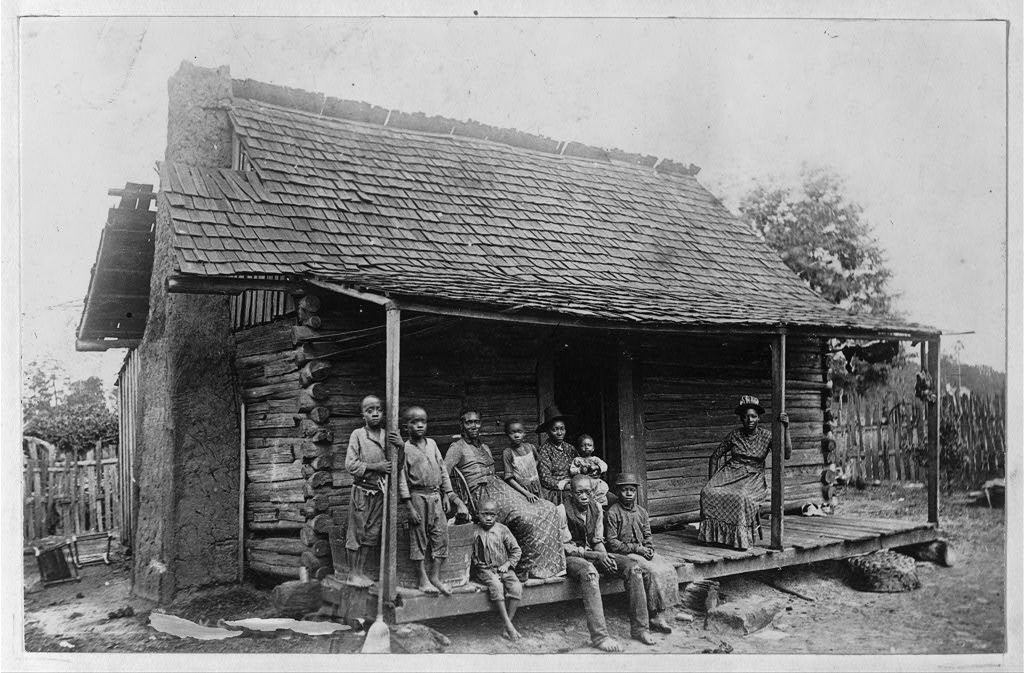

When delegates came together in June of 1901, they followed in the footsteps of states like Mississippi and Alabama that had legislated discriminatory laws, expanded criminal disenfranchisement, and introduced arbitrary voting eligibility requirements such as literacy and good character tests. These laws had a devastating and intentional impact on the Black vote. Virginia did the same with the goal of “eliminat[ing] the darkey as a political factor in this state in less than five years, so that in no single county…will there be the least concern felt for the complete supremacy of the white race in the affairs of government.” The photo shows Black members of Virginia’s General Assembly in 1887/1888. Only a few years later, the General Assembly was all white.

1902

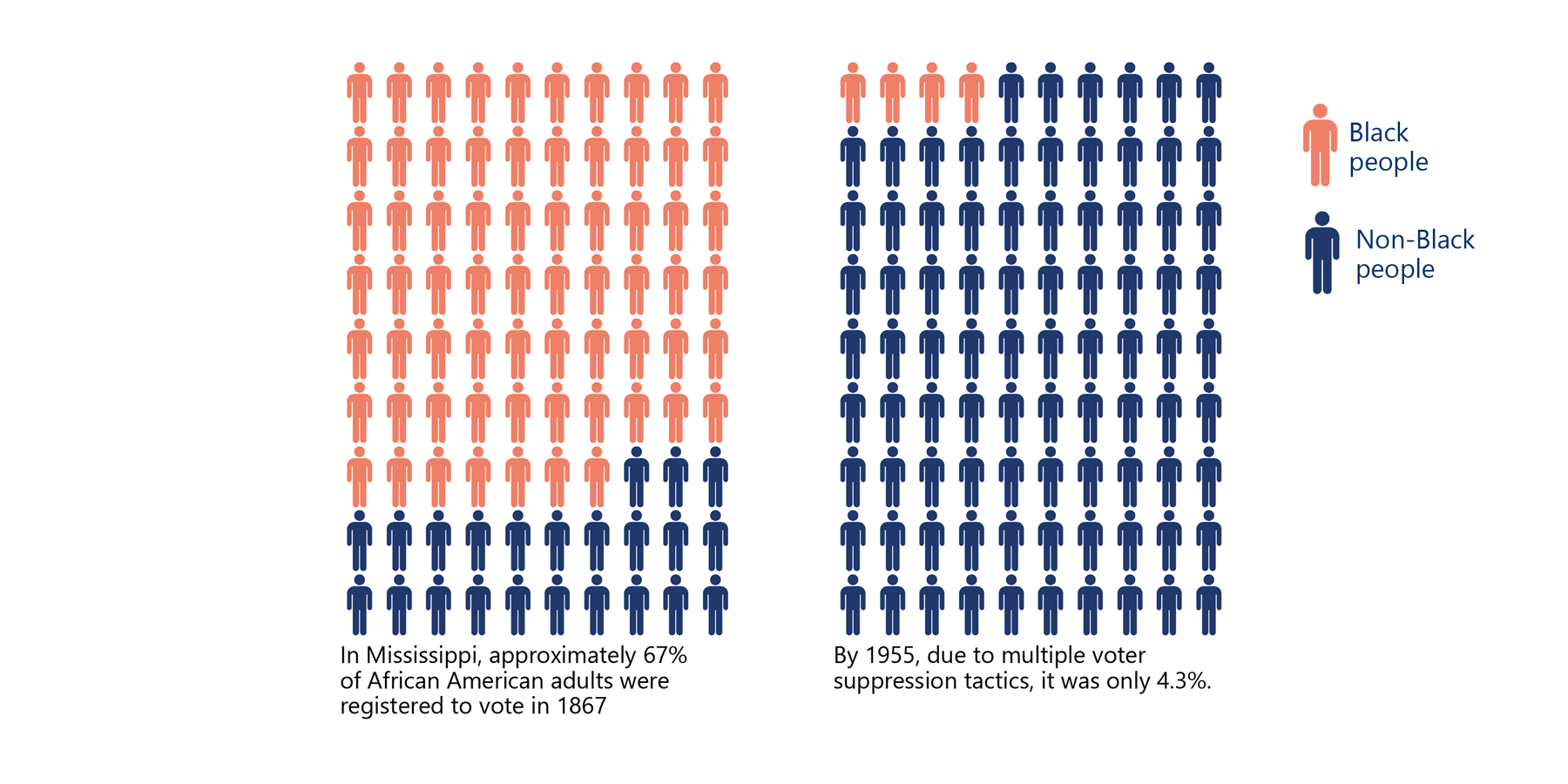

After the ratification of Virginia’s new constitution in 1902, Black turnout dropped 90%. The reinstatement of the poll tax, the adoption of a literacy requirement, and the addition of “any felony” conviction to the list of disqualifications to vote, among countless other suppression tactics, had an immediate and devastating effect on Black voters. These voter suppression efforts were combined with cruel and horrific acts of racial terror across the South -all in an effort to keep Black voters from exercising their right to vote by any means. In Mississippi, approximately 67% of African American adults were registered to vote in 1867. By 1955, it was only 4.3%.

The next 60 years played out as it was designed – Black voters were rampantly disenfranchised and blocked from gaining significant social or political power nationwide, but especially in the South. By the 1940s, it was estimated that 10 million Americans were disenfranchised simply because they could not pay the poll tax in their state. No substantive changes came until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which reduced the voting age from 21 to 18 and instituted many reforms geared toward scaling back these discriminatory actions.

1940

It was not until 1940, on the heels of media investigations and other reports of the horrific conditions being endured by “leased convicts,” like the one on the right reported in the Birmingham News, that the practice of convict leasing or peonage was abolished. While this ended the wholesale practice of people who were incarcerated being “sold” to plantations, mining, railroad, steel, and other companies, it did not end the practice of using people in prisons for free labor, which still exists today.

1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibited racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement on August 6, 1965, and Congress later amended the act five times to expand its protections. Designed to enforce the voting rights guaranteed by the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, the act secured the right to vote for people of all races throughout the country, especially in the South.

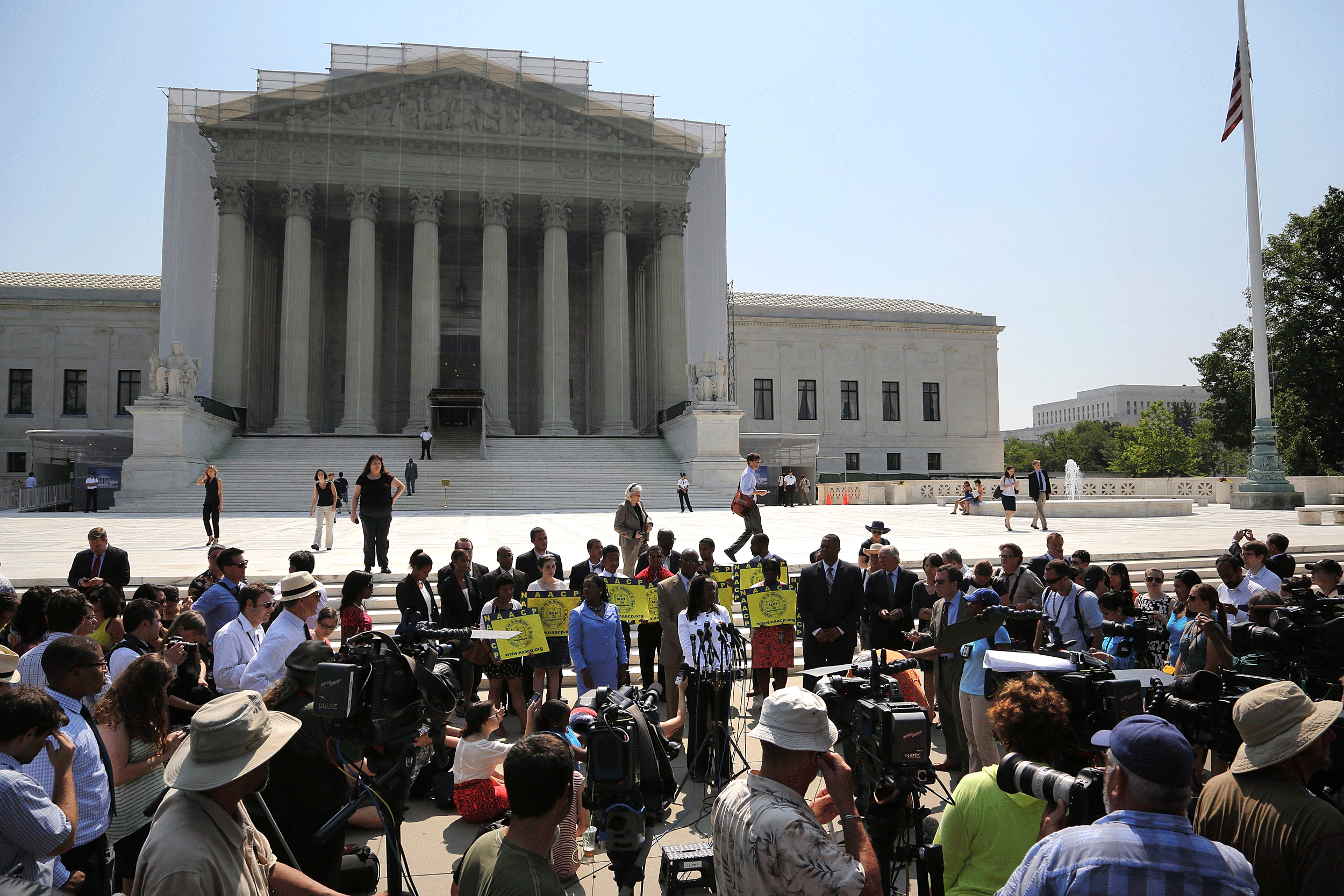

2013

In the 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court invalidated a decades-old “coverage formula” naming jurisdictions that had to pass federal scrutiny of their voting laws under the Voting Rights Act. Due to these jurisdiction’s history of discrimination, in order to pass any new elections or voting laws they would need to have what is referred to as “preclearance.” Not surprisingly, many states adopted voter identification, voter registration laws, and voting processes that made voting harder, especially for poor people, people of color, and elderly people. Virginia signed into law a photo-ID requirement that eliminated many forms of previously acceptable IDs – a law which stayed in place until July 2020.

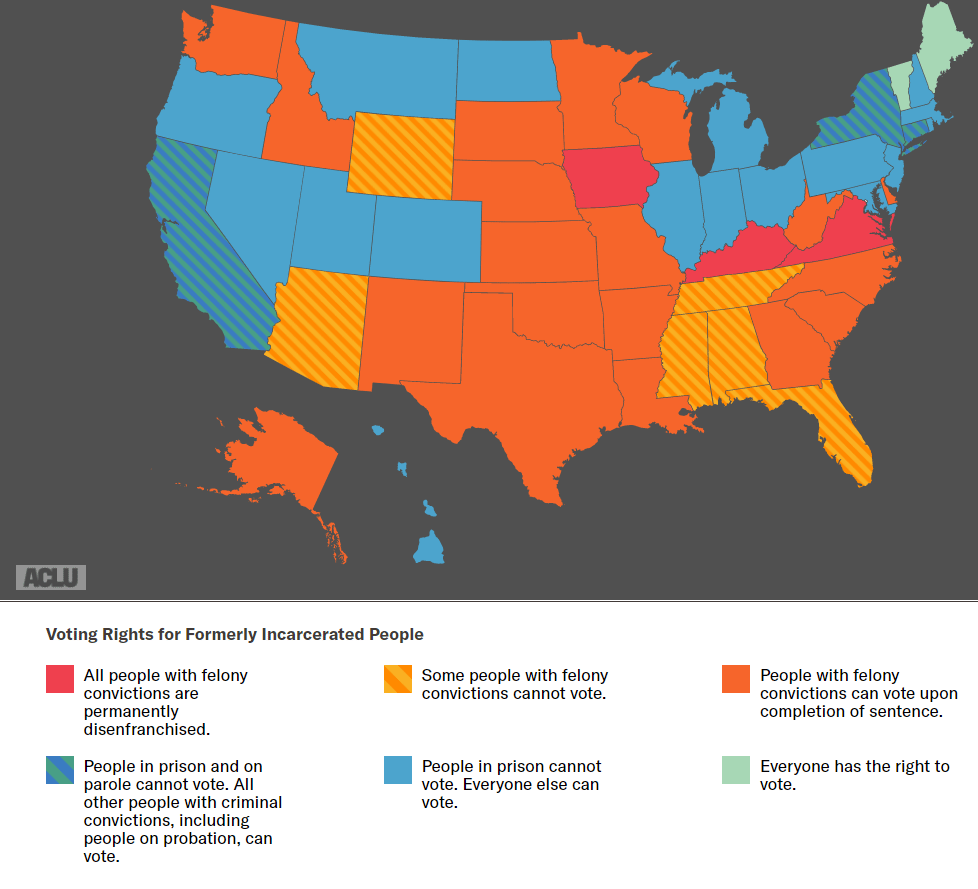

The authority to restore voting rights lies only in the governor’s hands, a right assigned to the role in the 1868 Constitution. While the total number of people who remain disenfranchised in Virginia is likely lower due to individual rights restoration work that happened after 2016, there is still a large disenfranchised population, and we are still stripping every person convicted of a felony of their right to vote. That is adding approximately 12,000 new people per year to the disenfranchised population. To this day, Virginia remains one of only three states that permanently disenfranchises people with a felony conviction, maintaining one of the longest legacies of racial discrimination at the ballot box in America.

While Virginia has done work to rid its current constitution of some of these explicitly racist ideas, it is far from done. Felony disenfranchisement was not highly debated in 1902 - it was considered a given that Blacks were more likely to be convicted of crimes. Hundreds of thousands of Virginians have been disenfranchised as a result of a felony conviction. The vast majority are Black, out of prison, and off probation. These are everyday people, people like you and me, who have had their political voice silenced because of a Commonwealth that refuses to shed itself of its racist roots.