In preparation for Black History Month, I did a little research and uncovered some fascinating people like Addie Waites Hunton, an African American suffragist, activist, writer, political organizer, and educator.

Early Life

Born in Norfolk on June 11, 1866, Addie D. Waites lost her mother as a child and then moved to Boston to be raised by a maternal aunt. She was the first black woman to graduate from Philadelphia’s Spencerian College of Commerce. Waites then moved to Normal, Alabama, where she taught at the State Normal and Agricultural College (now Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University).

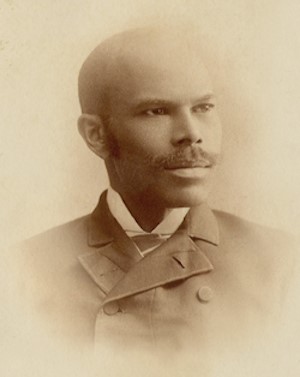

Marriage and Early Civic Work

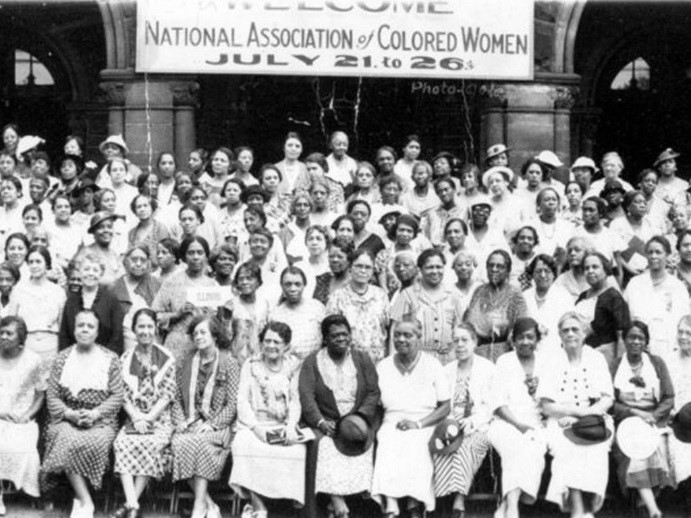

In July 1893, she married William Alphaeus Hunton, who had come to Norfolk in 1888 to found and become secretary of a Young Men’s Christian Association for Negro youth. During the first years of her marriage, Hunton worked full time and also was her husband’s secretary. She became a member of the National Association of Colored Women, attending the 1895 founding convention in Boston as a delegate from the Woman’s League of Richmond.

After living in Norfolk and Richmond, in 1899 the Huntons moved to Atlanta, Georgia. She had four children, but only two survived infancy. After the 1906 Atlanta race riot, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where the Huntons continued their activism. In 1907, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) appointed her secretary to work among black Americans. She toured the South and Midwest, attracting prominent black women to the YWCA.

Around August 1902, Hunton addressed The Negro People’s Christian and Educational Congress in Atlanta. Her talk was entitled “A Pure Motherhood: The Basis of Racial Integrity.” She began with:

This great and unique Congress has rightly discerned the signs of the times inasmuch as it has given due recognition to the women of the race. For, in the discussion of these problems affecting the highest and purest development of our people, the relation of woman to that development cannot be ignored.

Hunton said women had shown their leadership in the church, in social and moral reforms, and in the business world. “To woman is given the sacred and divine trust of developing the germ of life….Upon the Negro woman rests a burden of responsibility peculiar in its demands.” Hunton called upon the “intelligent mothers of the race…to concentrate their efforts… [to] diminish the number of poorly born poorly bred and deformed children…out on the streets….”

From 1906 to 1910, she was a countrywide organizer for the National Association of Colored Women (NACW).

Confronting Racism in World War I

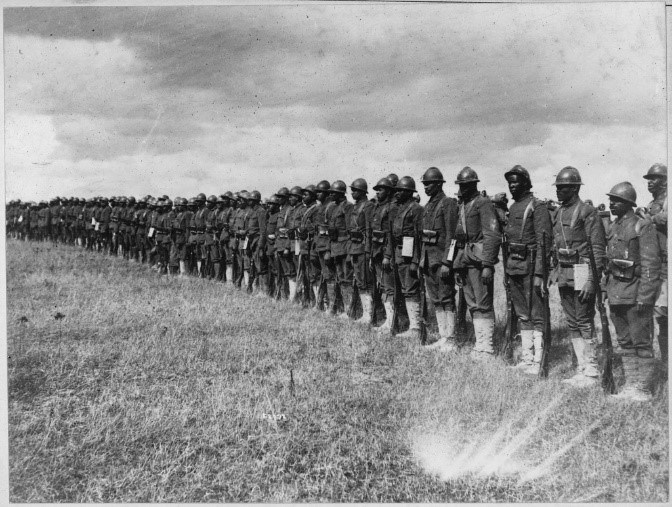

After her husband died in 1916, Hunton became involved in the YMCA’s work abroad during World War I. She set sail for France in June 1918. Hunton was assigned along with Kathryn M. Johnson and Helen Curtis to work with the 200,000 segregated black troops stationed there. They were the only three black women assigned to this duty. Hunton’s initial assignment was at the supply and transport center of St. Nazaire where she added a literacy course and a popular Sunday evening discussion program to the typical YMCA canteen, movies, and other services.

In January 1919 Hunton was transferred to a rest and relaxation area in southern France. There she assisted in organizing an educational, religious, athletic, and cultural activities program for over a thousand black troops on leave who arrived weekly. Her most demanding assignment started in May when she was assigned to the military cemetery at Romagne, near Verdun where black soldiers were tasked with reburying Americans killed in the Meuse-Argonne battle. She described the work as a ‘“a gruesome, repulsive and unhealthful task, requiring weeks of incessant toil during the long heavy days of summer.’” She also recounted how the undercurrent of resentment among the soldiers created a constant sense of danger. Hunton wrote: ‘”Always in those days there was fear of mutiny. We felt most of the time that we were living close to the edge of a smoldering crater.’” [“Addie D. Waited Hunton,” https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hunton-addie-d-waites-1875-1943]. Hunton’s last assignment took her to Brest (https://youtu.be/V5S8kdrQYxE) where she worked for six weeks among soldiers awaiting transport home. She returned to America in the autumn of 1919.

Activist Against Racisim

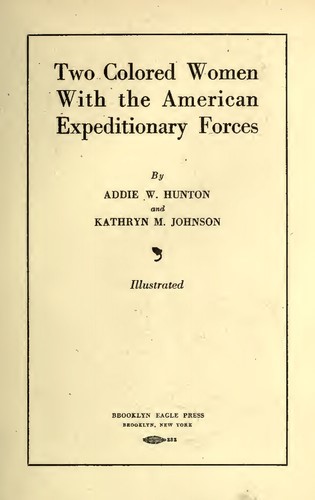

While in France, Hunton saw the racism against black soldiers and the regulation of their lives, reminiscent of Jim Crow. In 1920, Hunton and Johnson wrote about their experiences in Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces. The following is an excerpt:

“These truly are the Brave, These men who cast aside Old memories, to walk the blood-stained pave Of Sacrifice, joining the solemn tide That moves away, to suffer and to die For Freedom — when their own is yet denied!” [p.94]

Hunton ‘”witnessed repeated instances of officially sanctioned racial prejudice; Negro recruits had been systematically assigned to menial tasks, barred from fraternizing with the white American troops….She also notes [in her memoir], however, that the Negroes in the A.E.F. [American Expeditionary Force] ‘developed in France a racial consciousness and racial strength that could not have been gained in a half century of normal living in America’….’” [areamericana.com/pages/books/3728436/addie-w-hunton-kathryn-m-johnson-1875-1943-1878/two-colored-women-with-the-american-expeditionary-forces?soldItem=true]

After returning home Hunton became a field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Suffragist

Hunton also was a leading suffragist. Although the 19th Amendment granted women the vote, not all women had equal access to voting. (https://youtu.be/XcrGQ0npuCw). Black women faced obstacles like trying to register to vote. This was true in Virginia.

In October 1920, the NAACP sent Hunton to the Hampton Roads region to find out about reports that ”colored women” were not being registered. [Brent Tarter, et al., The Campaign for Woman Suffrage In Virginia, 149] Women in Hampton and in nearby Phoebus told her they had to make numerous trips to the registrar’s office before successfully registering; a few women simply gave up. Some white registrars gave white women priority or prolonged the process for black women. These registrars occasionally offered black women blank sheets of paper instead of the forms they provided to white women. Sarah Haws Baker Fields told of being asked questions like: ‘”Who are exempted from paying poll tax and yet eligible to vote?’” [Brent Tarter, et al., The Campaign for Woman Suffrage In Virginia, 150] Fields’ husband, respected black lawyer George Washington Fields, helped women to register and assisted Hunton’s investigation.

Hunton discovered an even graver situation in Norfolk. The local registrar refused to register well-known civic and fraternal leader Emma Virginia Lee Kelley and four others ruling they had answered incorrectly his questions. His attempt to intimidate Kelley and other black women backfired when he could not answer his own questions correctly.

In 1920, the NAACP presented proof to Congress of discrimination against black female voters. Hunton, an executive officer, was among them. She and four other members gave testimony at a congressional hearing relating to the Tinkham Bill reducing congressional representation from states where women were restricted from voting. Although Hunton and the others produced a lot of evidence, the bill failed to pass.

Hunton supported black women voters at the National Woman’s Party convention in 1921. Black women frequently were not allowed to speak at the party’s meetings. The party’s leader, Alice Paul, claimed there was no room on the schedule. When black women did speak others severely criticized them. Consequently, black women became more and more exasperated by the inadequate attention to their concerns. Hunton headed a delegation of sixty black women from fourteen states urging Paul to make the race question a major issue. She thought Paul was antagonistic to the cause of black women. Mary Church Terrell asked Paul whether or not she supported enforcing the Nineteenth Amendment for all women; Paul did not answer.

Other Civic Activities

As a member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Hunton visited Haiti in 1926 to survey America’s occupation. She wrote the chapter on race relations in the committee’s report, Occupied Haiti. Hunton was one of the principal organizers of the 1927 Fourth Pan-African Congress in New York City. She also served as president of the International Council of the Women of Darker Races and of the Empire State Federation of Women’s Club.

In 1938, she published, William Alphaeus Hunton A Pioneer Prophet of Young Men, a book about her husband’s life and work. Hunton’s last public activity was at the 1939 New York World’s Fair where she officiated at a ceremony honoring exceptional Negro women.

Hunton died in Brooklyn on June 21, 1943, having devoted her life to matters of racial and gender equality.

For more information see https://youtu.be/kuJUT-Ip70c.