Part II: Virginia’s Native Americans

Virginia’s Earliest Inhabitants

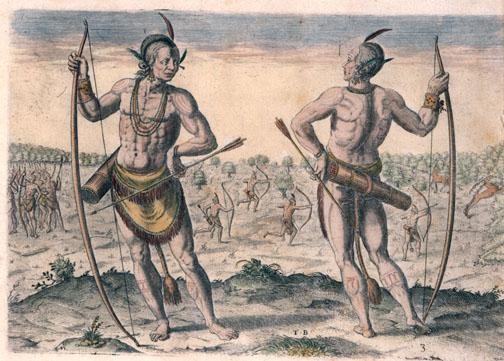

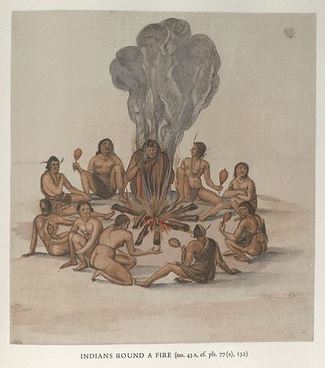

Virginia’s earliest inhabitants were hunters and gatherers who tracked the migratory patterns of animals. In time, they formed towns along riverbanks and sketched out their homelands, growing close, stable affiliations with the animals and their environment. These hunters, fishermen, and farmers established intricate social and religious orders and extensive trade networks.

As the University of Oklahoma Press writes, author and VCU history professor Gregory D. Smithers “brings this world to life in Native Southerners [Indigenous History from Origins to Removal], a sweeping narrative of American Indian history in the Southeast from the time before European colonialism to the Trail of Tears and beyond.” Lynette Allston, Chief of the Nottoway Indian Tribe thinks “Native Southerners is a journey through centuries of southern Native American history. This thoughtful and sensitive narrative offers a compelling perspective on the clashes between Natives and Europeans, which forever changed the lives of the southern Native population.” Check out Native Southerners at the Richmond Public Library.

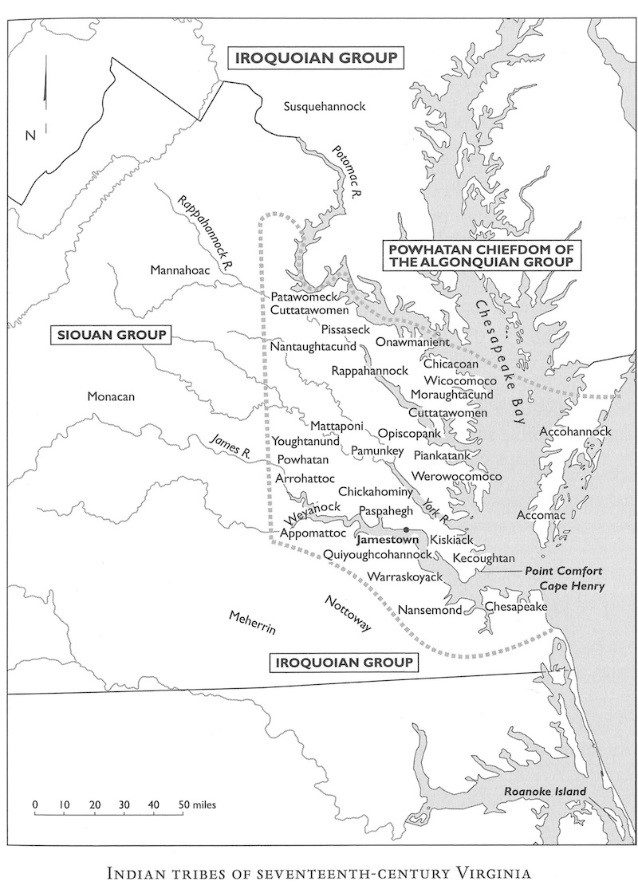

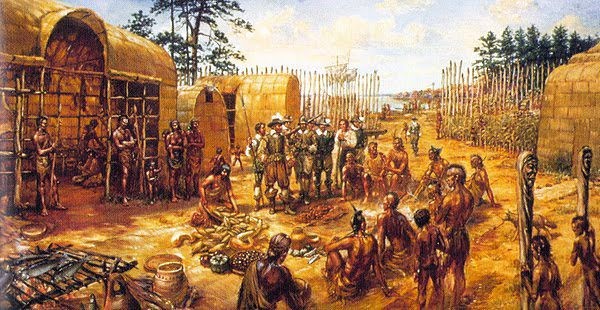

During the late 16th century through the 17th century, three diverse tribes controlled the region now known as Virginia – the Powhatan, the Monacan and Cherokee. They spoke three distinctive languages – Algonquian, Siouan and Iroquoian, and lived along the banks of the coastal waterways, in woodlands and mountain valleys. Researchers know most about the Algonquian-speaking Indians of Tsenacomoco, also known as the Powhatan paramount chiefdom (28 to 32 tribes). Led by Powhatan, the society eventually included a number of chiefdoms and tribes led by men and women, extending from the James River to the Potomac River.

When the English landed at James Island in 1607, Virginia’s Indigenous peoples numbered around 50,000. Powhatan’s paramount chiefdom encompassed 6,000 square miles and included approximately 14,000 of the 20,000 Algonquian-speaking Indians. Numerous historians think Powhatan began consolidating the Algonquian-speaking districts in the 1570s in an effort to create a joint force against Iroquoian-and Siouan-speaking districts to the north, west, and south as seen in the map below.

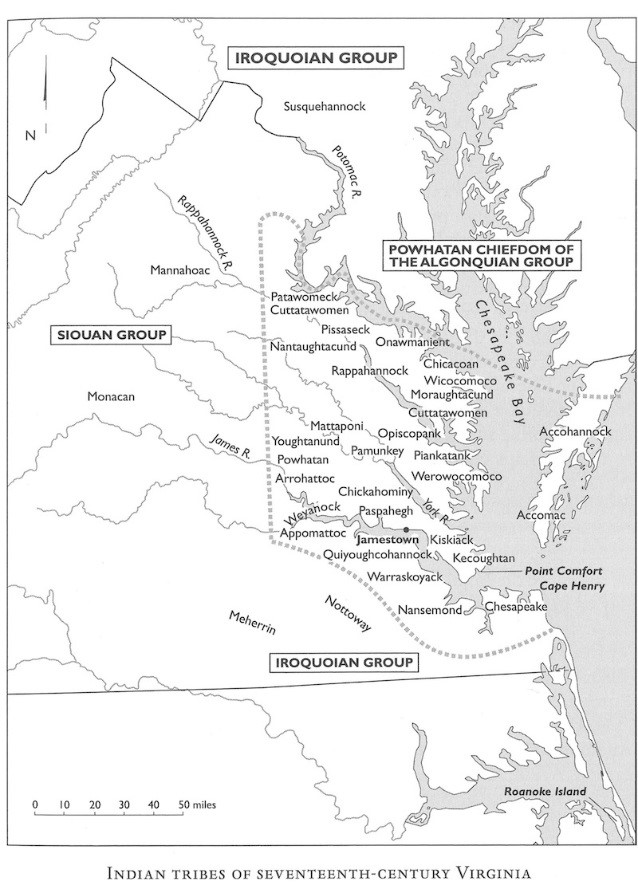

Early Anglo-Indian Interaction

The arrival of Englishmen forever changed Indian life. “The first century of Anglo-Indian interaction in Virginia can be understood as a prolonged period of adjustment for both the Native inhabitants and the European settlers.”(National Park Service, A Study of Virginia and Jamestown: The First Century, Edward Ragan, Chapter 6: A Brief Survey of Anglo-Indian Interactions in Virginia during the Seventeenth Century at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/jame1/moretti-langholtz/chap6.htm.) Disease devastated them. After three years of dealing with English haughtiness and mistreatment, Virginia’s Indian people were done. The Powhatan thought that the benefits of trading with the English were not worth the resulting hardships. So, in 1609 began the first Anglo-Powhatan War. Eventually, they were defeated militarily. “Once defeated, tribal communities were subjugated politically under the English crown and categorized racially under Virginia law.”(National Park Service, A Study of Virginia and Jamestown: The First Century, Edward Ragan, Chapter 6: A Brief Survey of Anglo-Indian Interactions in Virginia during the Seventeenth Century at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/jame1/moretti-langholtz/chap6.htm.) Although the legislature allocated land for the tribes of Tsenacomoco, some were driven away while others groups disbanded or dissolved as part of the Native American Diaspora.

Dr. Smithers also has written The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity.

In subsequent years, Native Americans tried to maintain their traditions while combating “disease, hunger, forced relocations, and restrictive colonial and later statewide policies that curtailed their rights to travel unmolested through lands now occupied by settlers, to visit their traditional hunting and fishing grounds, and to testify in court on their own behalf.” (Brendan Wolfe, “Indians in Virginia,” https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/indians_in_virginia)

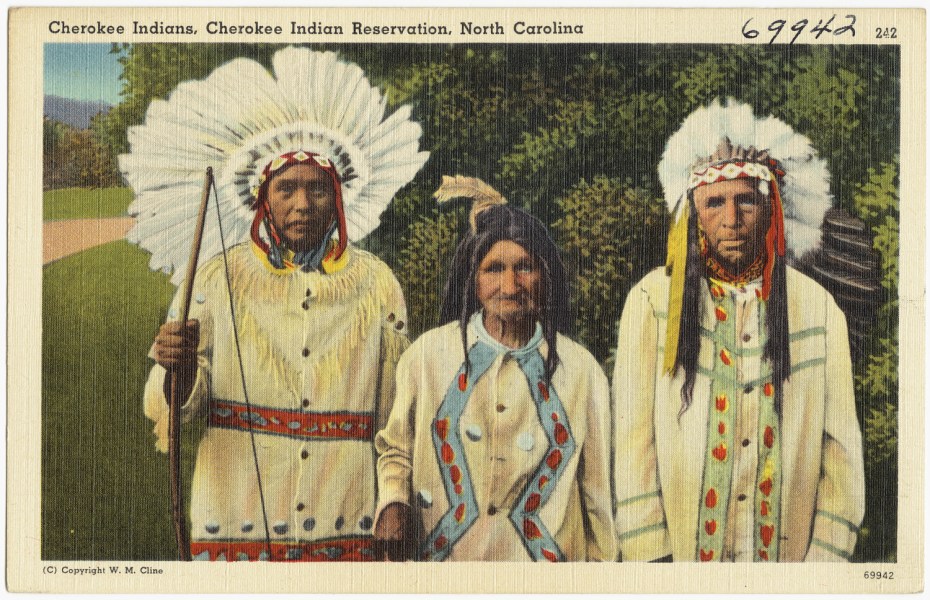

At the dawn of the twentieth century, “a cultural renaissance bloomed and some scholars began to study Indian history more closely.”Brendan Wolfe, “Indians in Virginia,” https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/indians_in_virginia)

On June 2, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, ending a lengthy federal dispute and fight over comprehensive birthright citizenship for American Indians.

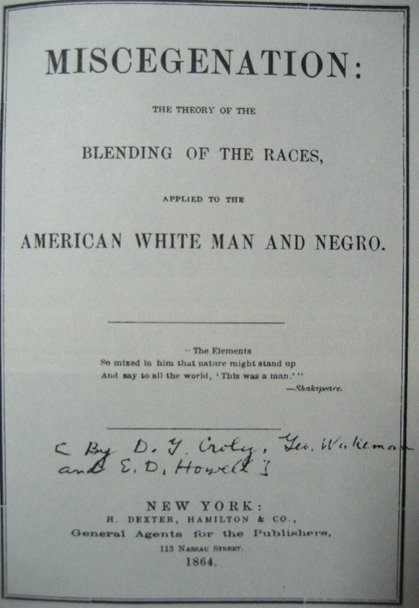

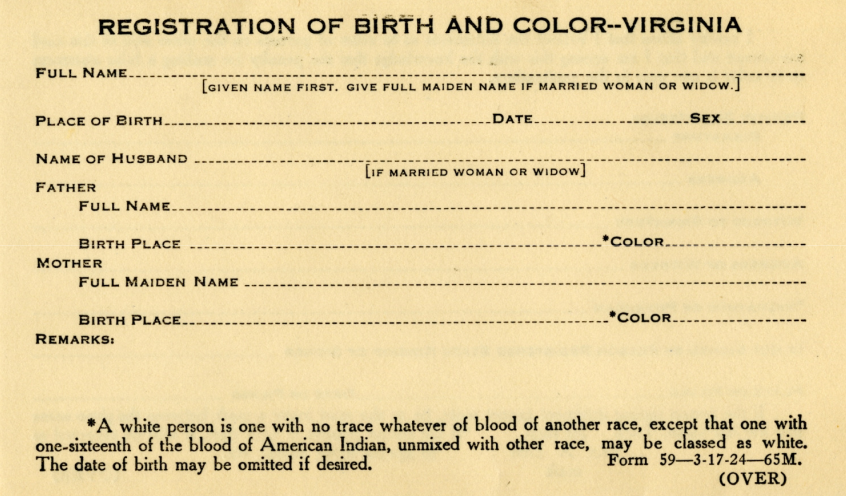

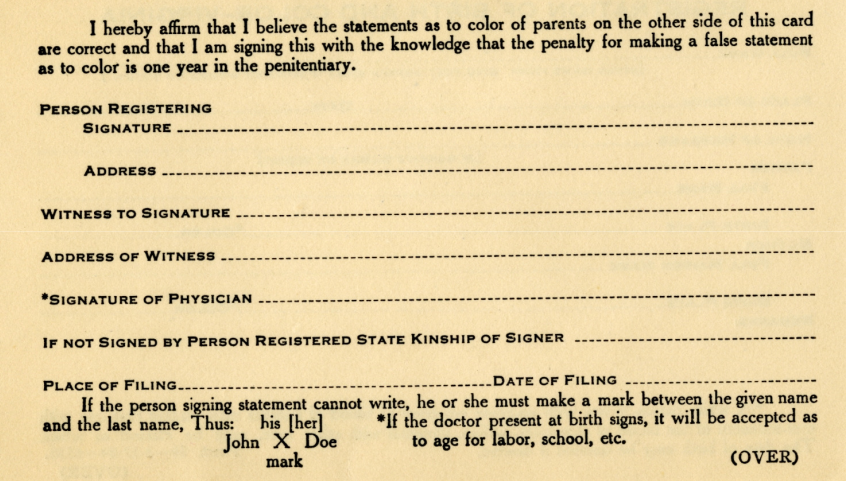

Meanwhile, Virginia moved to strip Native Americans of their identity. The same year Native Americans were granted citizenship the Virginia legislature passed several “racial integrity laws” to safeguard ‘”whiteness” against what many Virginians perceived to be the negative effects of race-mixing” – miscegenation. First, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 “made it illegal for white people to marry anyone other than another white.” According to Anthropologist Helen Rountree of Old Dominion University, “that meant native Virginians as well as others were forced to classify themselves as colored.” Second, the Public Assemblages Act of 1926, dictated that all public meeting spaces were to be segregated. In “Colored persons and Indians defined” the General Assembly in 1930 codified the definitions of “colored persons and Indians.”

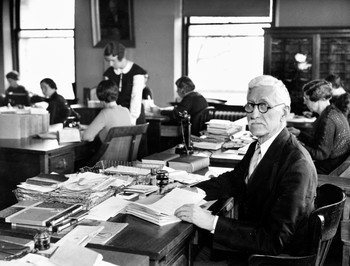

Virginia State Registrar of Vital Statistics Walter A. Plecker zealously enforced the Racial Integrity Act, regularly fretting that blacks were trying to pass as white. Roundtree stated: “He could actually stop marriages if Indian people insisted on being registered as Indian, rather than colored”

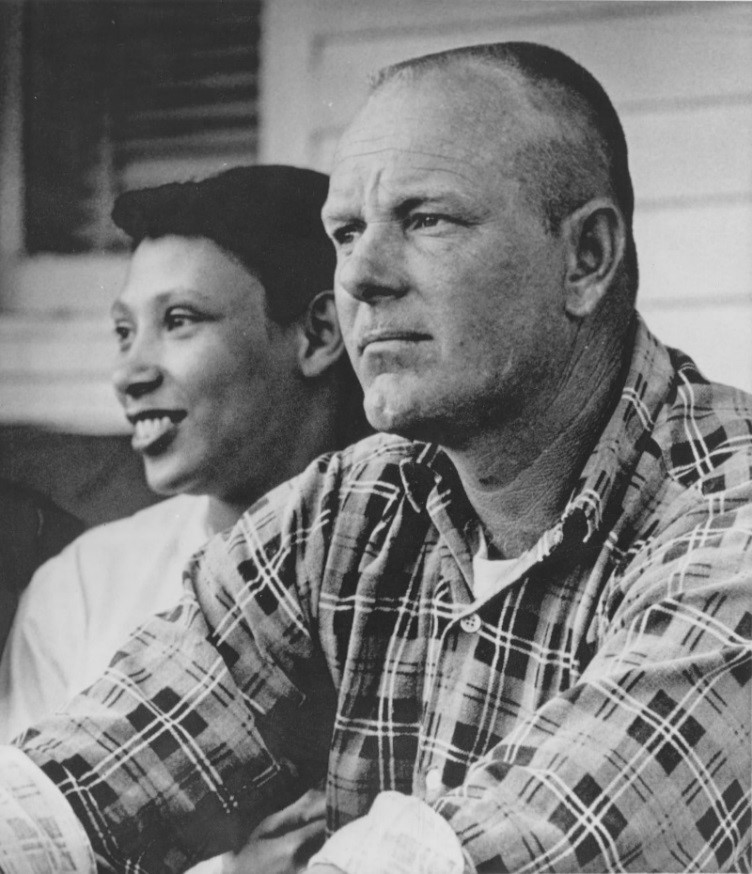

The Racial Integrity Act remained in effect until 1967. That year the U.S. Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia ruled unanimously that “anti-miscegenation” statutes were unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. The decision frequently is considered to be a turning point in unravelling Jim Crow race laws. The plaintiffs were Richard and Mildred Loving, a white man and a woman of mixed African American and Native American heritage, whose marriage was considered illegal according to Virginia state law. They had been arrested on July 11, 1958, only five weeks after their wedding and indicted on charges of violating Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law, which made interracial marriages a felony. They had begun their legal battle in 1963 when Mildred Loving wrote U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy for assistance. He referred the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union, which agreed to take their case. See the following link for an interview with the Lovings: https://youtu.be/FahZ4IbVYY. Also, click this link to the 2016 movie trailer for The Loving Story, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1759682/. In 2001, Virginia’s House Joint Resolution No. 607 condemned the Racial Integrity Act and eugenics as racist.

Today

“Native peoples recognize not only the connection between the past, present, and future, but also the innate connection we have to each other as people. While Virginia Indian stories relate experiences that were lived by tribal members, that history is not exclusive; for better or for worse, the history of Virginia Indians is our history. As more stories are told, as more of our shared history is learned, we will begin to create an understanding of who we are today, not only as Virginians and Americans, but as human beings.” (The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail, Edited by Karenne Wood, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, Second Edition, 2008.)

Virginia’s State Recognized Tribes

Virginia’s State recognition process is meant to acknowledge Native American tribes that preceded European colonization. Virginia has used various measures and criteria for conferring state recognition. English colonization and the resulting diaspora meant that most of the tribes here before 1607 were unable to meet the criteria. The Commonwealth officially recognizes by either executive or legislative action the following 11 organized groups:

Mattaponi (Mattaponi River/King William County),

Upper Mattaponi (King William County)

Pamunkey, (Pamunkey River/King William County)

Eastern Chickahominy (New Kent County),

Chickahominy (Charles City County)

Rappahannock, (Indian Neck/King & Queen County)

Nansemond (Cities of Suffolk and Chesapeake)

Monacan Indian Nation (Bear Mountain/Amherst County)

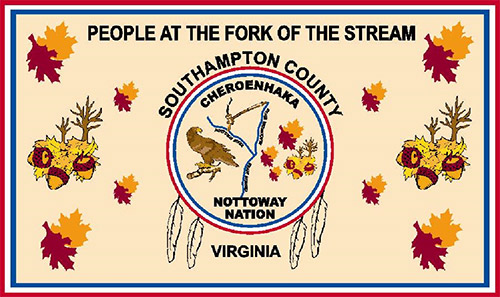

Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), (Courtland/Southampton County)

Nottoway of Virginia, (Capron/Southampton County)

Patawomeck (Stafford County)

In 2016, the legislature passed and the Governor signed HB814, allowing the Secretary of the Commonwealth to create a Virginia Indian Advisory Board. The advisory board counsels the legislator and Governor on non-recognized tribes seeking recognition.

Only the Pamunkey (http://pamunkey.org/reservation/) and Mattaponi (https://www.mattaponination.com/) have state recognized reservation lands allocated by 17th century colonial treaties. There are no federal reservations for Virginia’s Native Americans because no treaties were signed between the tribes and the federal government to end a war.

Since the late 20th century, many of the tribes began to press for federal recognition. In 2016, the Pamunkey Indians became the first Virginia tribe to be granted the status. In 2018, H.R. 984, the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 recognized the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Monacan and Nansemond tribes as sovereign nations, bringing to 573 the number of federally-recognized tribes in the U.S. As such, the tribes can now create their own laws, collect taxes and manage their lands.

Thomasina Elizabeth Jordan, also known as “Red Hawk Woman” was an American Indian activist and one of the first Native Americans to serve in the U.S. Electoral College.

U.S. Congressman Rob Wittman (VA-01) who introduced the bill remarked: “Today we celebrate a decade of hard work. Our ‘first contact’ tribes of the Commonwealth of Virginia will finally receive the recognition they deserve….This is an issue of respect; federal recognition acknowledges and protects the historical and cultural identities of these tribes. Not only will it affirm the government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Virginia tribes, but it will create opportunities to enhance and protect the well-being of tribal members.”

“Virginia Indian tribes seek to cultivate their own cultural identity while educating other Virginians about their history. They do this through tribal cultural centers, annual Pow Wows (https://youtu.be/ZxN35hTIPl0; https://youtu.be/miVJQHx1A9U) and educational outreach. The Virginia Indian Heritage Program at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities also works with and on behalf of the state’s tribes. According to its mission statement, the program exists to “help redress centuries of historical omission, exclusion, and misrepresentation.”

“For our elders and ancestors, whose voices were silenced but whose courage created us.” The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail.

Check out these links for more information about Virginia’s Native Americans:

There are many more links to explore!