The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on August 18, 1920, gave women the right to vote. Section 1 reads:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Behind this simple yet profound statement was almost a century of protest beginning on the national stage in June 1848 with the New York Seneca Falls Convention. After the convention, the demand for the vote became a cornerstone of the women’s rights’ movement. But, even before the convention many American women insisted on a more equitable place in American society. They questioned, resisted the social norm that women’s role was the obedient wife and mother whose focus was the family and home. Women began stepping outside the domestic sphere, becoming involved in reform movements like the abolition of slavery. Deprived of basic civil rights only men possessed, they clamored for educational and employment opportunities and the vote. Votes for women translated to broad social change which helps explain the long arduous struggle.

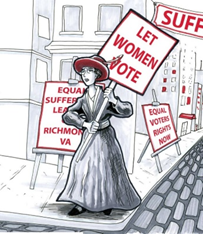

Unlike their sisters to the West and North, Southern women were more hesitant to organize and join the suffrage movement largely due to local government opposition and social mores. In Virginia, the first organized movement did not occur until 1870. The third organization, the Equal Suffrage League, in time realized it had to change its strategy and like other women’s groups fought for a federal amendment to the constitution.

Kansas Senator Samuel Pomeroy enthusiastically campaigned for the measure. “I have gone boldly—fearlessly—into the movement! And it must succeed!” In December 1868, he introduced a resolution to amend the Constitution. The Senate agreed to let Pomeroy’s bill ‘lie upon the table,’ and there it remained, never to be taken up again.” Ten years later a woman’s suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress and rejected. For the following 41 years, the amendment was reintroduced each year and scrapped.

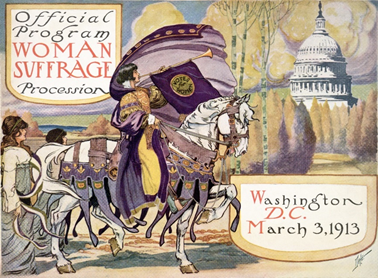

As momentum for a constitutional amendment grew, in 1913 women marched in Washington, DC. Among the marchers were Virginia women like novelist Mary Johnston who spoke at one of the closing events.

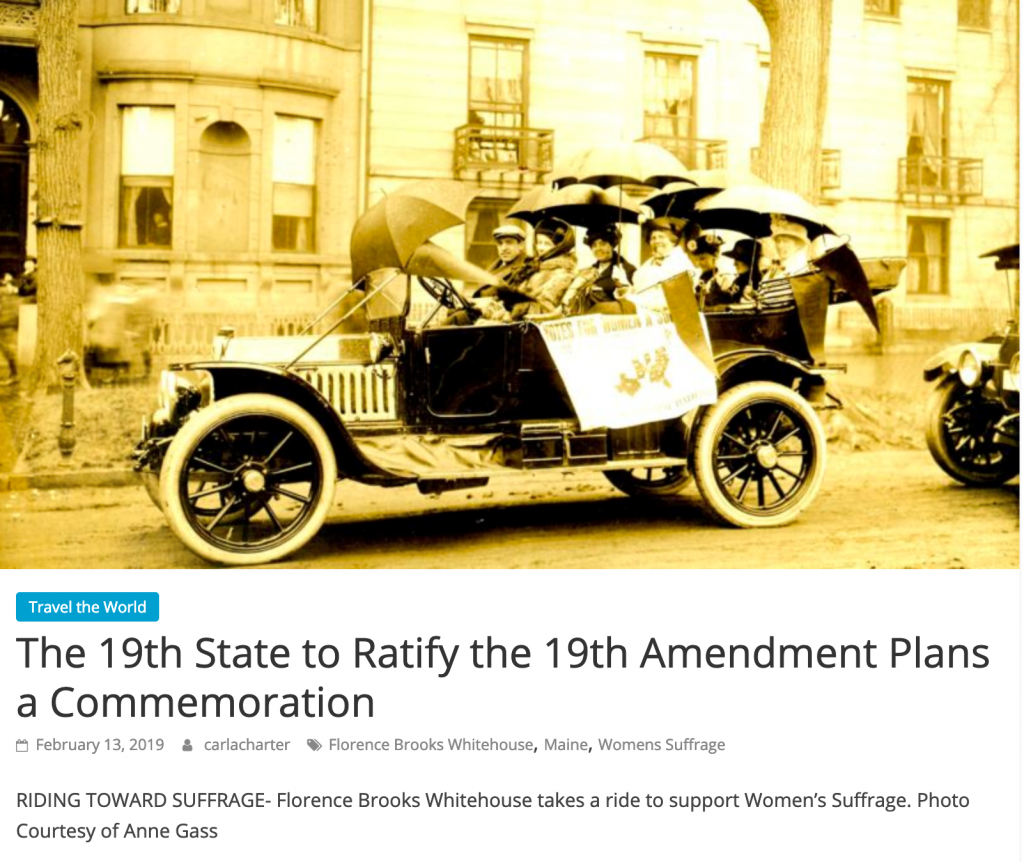

In the spring of 1914, the Senate’s Committee on Woman Suffrage approved a federal suffrage amendment, but it failed to pass in the full Senate. The House of Representatives had the measure tied up in committee. The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage responded to the stalemate by organizing concurrent demonstrations across the country for May 2. The National Association Woman Suffrage Association decided to participate as did Virginia’s Equal Suffrage League which held rallies in Richmond’s Capitol Square, in Norfolk, Williamsburg and in Lynchburg. The House Committee on Rules refused to place the amendment on the calendar. Virginia suffragists Pauline Adams, Sophie Meredith, Mary Lockwood and others decorated a car with banners and drove to Washington, DC to meet with the chair of the Rules Committee. They couldn’t convince the Texas Democrat to budge. Like other southern Democrats he opposed the amendment believing it endangered state’s rights and their ability to restrict African American voting. Undaunted, Virginia suffragists joined national associations to continually put pressure on Congress to act.

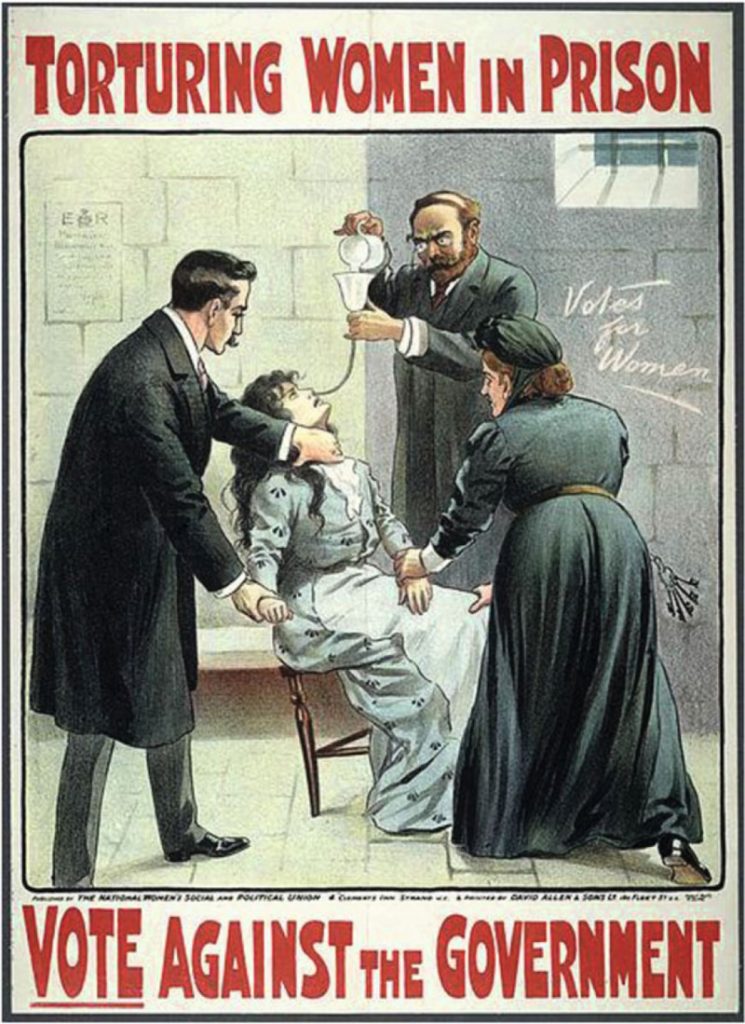

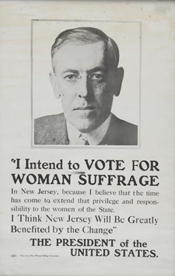

From June to November 1917, a number of nationally known suffragists like Alice Paul and Lucy Burns were arrested while picketing in front of the White House. The “Silent Sentinels” demanded President Woodrow Wilson give more than lukewarm “lip service” to their cause. People passing by frequently insulted and even attacked the women while police watched. Paul, Burns, and other women were imprisoned at the Occoquan Workhouse in Fairfax County. They joined Norfolk suffragist Pauline Adams and twelve of her followers who had been jailed there. All this because they wanted to vote!

Wilson and people across the country were shocked when they learned that many of these women were force fed after going on a hunger strike. In a September 30, 1918, Congressional speech President Wilson supported women’s suffrage. Recognizing the contribution of women during World War I, Wilson asked Congress, “We have made partners of the women in this war….Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” While the House of Representatives had approved a 19th amendment giving women the vote, the Senate had not voted on it.

In October, Wilson spoke to the Senate: ‘“I regard the extension of suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged.’” Still, the proposed amendment miscarried in the Senate by two votes. It would be another year before Congress took up the measure again. Finally,

Congress approved the 19th Amendment on June 4, 1919 and sent it to the states for ratification. By the end of the year, 22 of the required 36 states had ratified.

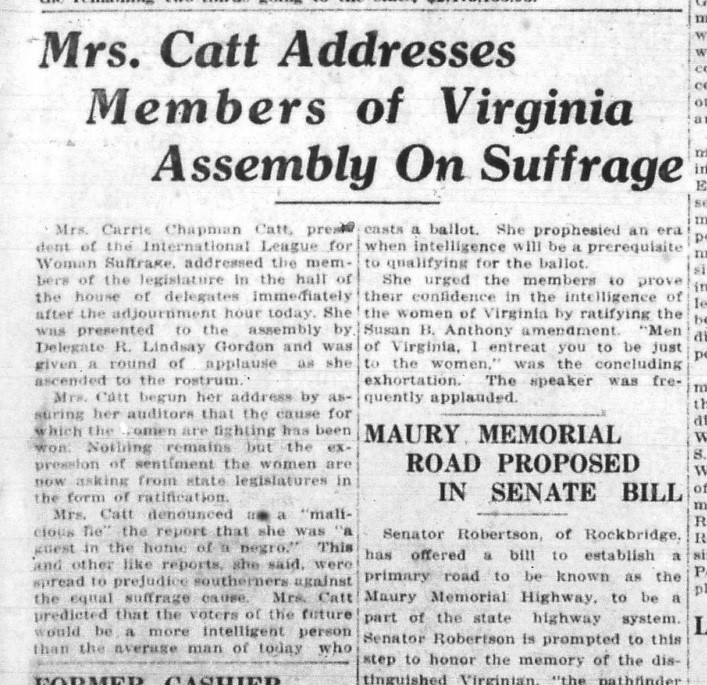

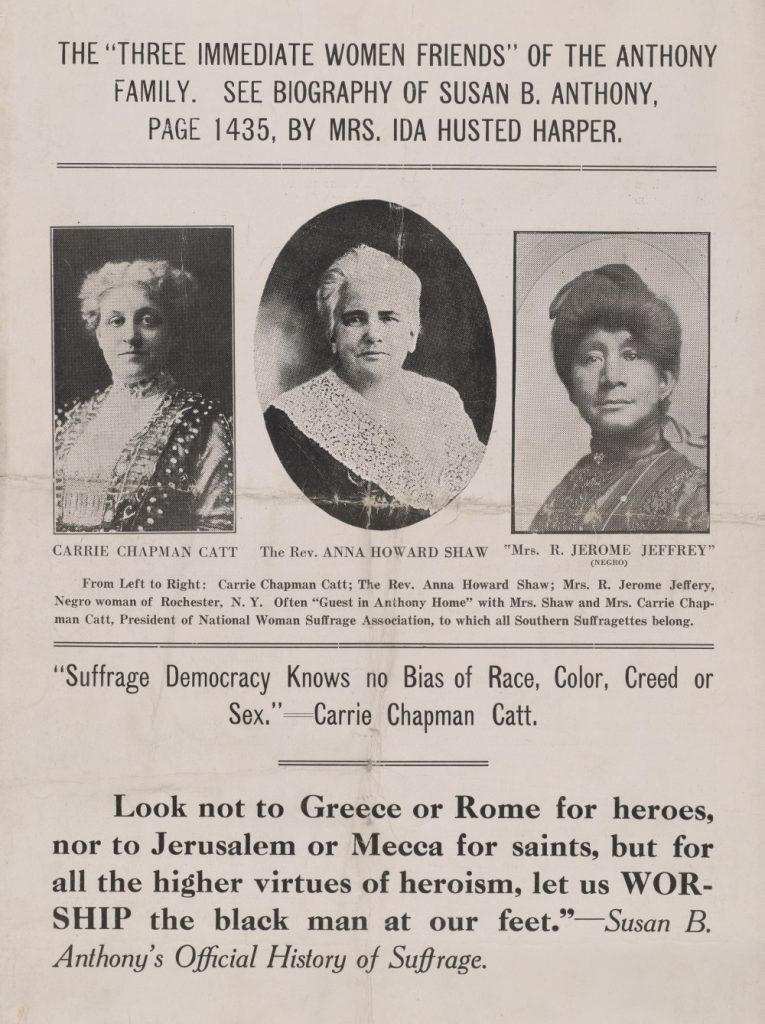

What would Virginia do? Realizing the stakes were high, Equal Suffrage League members and Virginia members of the National Woman’s Party appeared before the General Assembly when it met on January 14, 1920. On January 21, President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association Carrie Chapman Catt spoke to the House of Delegates; several Senators were there too. Anti-suffragists handed out a leaflet claiming woman’s suffrage would destroy white supremacy and that suffragists advocated racial equality.

The Richmond Evening Journal reported that that during Catt’s speech she ‘“denounced as a ‘malicious lie’ the [the anti-suffragists] report that she was ‘a guest in the home of a negro.’” Did Catt add that comment hoping to reassure anti-suffrage men that the challenging registration process would continue to limit the vote to educated and upright people? Catt said reports like this were intended to bias southerners against woman’s suffrage. She “predicted that voters in the future would be more intelligent ‘than the average man of today’ and ‘prophesied an era when intelligence will be a prerequisite to qualifying for the ballot.’” Concluding Catt stated: ‘“Men of Virginia, I entreat you to be just to the women.’” But, at least most of the men turned a deaf ear.

![[Cover]](https://rvalibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/BOOK-VA-SUFFRAGE-CAMPAIGN.jpg)

Check out The Campaign for Woman Suffrage In Virginia for more details

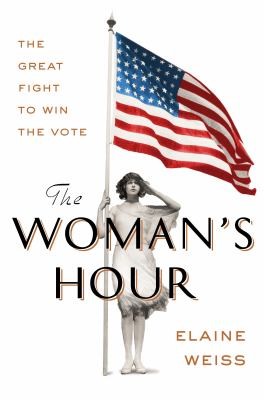

In the end, it came down to Tennessee. “The outlook appeared bleak, given the outcomes in other Southern states and given the position of Tennessee’s state legislators in their 48-48 tie.” The state’s decision rested on 23-year-old Republican Representative Harry T. Burn who was to cast the deciding vote. Burn opposed the amendment. But, his mother persuaded him to approve it. Mrs. Burn allegedly wrote to her son: “Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification.” With Burn’s vote, the 19th Amendment was ratified fully. The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight To Win The Vote by Elaine Weiss tells the story of the “furious campaign to secure the final state needed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment….”

On August 26, 1920, U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the 19th Amendment. At long last, women finally won the right to vote throughout America. On November 2, 1920, over 8 million women voted in elections for the first time.

“Voting is the most basic right of a citizen and the most important right in a democracy. When you vote, you are choosing the people who will make the laws.”