This is the second post in a two part series on the fight for woman suffrage in Virginia.

Before Virginia’s Coralie Franklin Cook published her 1915 article, “Votes for Mothers,” in the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, black female reformers in the 1880s had begun organizing their own women’s groups. In 1892, activist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, who had helped

found Boston’s Woman’s Era Club, issued a national “Call to Confer.” In July 1896, the women formed the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) at the First Annual Convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women. Ruffin told the convention’s attendees: ‘“The reasons why we should confer are so apparent…We need to talk over not only those things which are of vital importance to us as women, but also the things that are of special interest to us as colored women….’”

The NACW’s motto, “Lifting As We Climb,” embodied the group’s mission to promote women’s rights and to uplift and advance the position of black Americans When incorporated in 1904, the NACW became known as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). Activist Mary Church Terrell was the NACWC’s first president. Countless black women joined local clubs and organized at the national level. Over the next ten years, the NACWC participated in campaigns championing woman suffrage, combatting lynching and Jim Crow laws, and promoting other social reforms. By the time the U.S. entered World War I in 1918, the NACWC’s membership had grown to 300,000, the largest federation of local black women’s clubs.

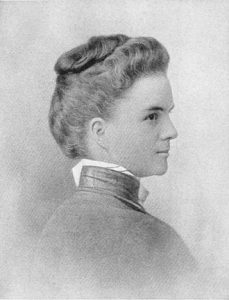

In 1907, educator and social reformer Janie Porter Barrett helped organize the Virginia State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs at the annual Hampton Negro Conference. Barrett was the organization’s president until 1932. Although records are scanty, we know the women talked

about suffrage at the federation’s annual meetings. At the July 1912 convention, Hampton and Norfolk members organized a suffrage parade. Seventy-two delegates heard Adella Hunt Logan ‘”mak[e] an excellent plea for an enlarged intelligence on the subject of woman suffrage through systematic study of civic problems.’” Delegates “declared in favor of full woman suffrage and advocated the formation of political study clubs’ for men and women.”

Virginia’s black suffragists did not pursue joining the all-white Equal Suffrage League (ESL). Why? In 1914, the St. Luke Herald (whose managing editor was Maggie Walker) put the situation in a nutshell: ‘“The women of the world are demanding and receiving the ballot; they are battling for it in every civilized country….In the South, white women want to join their sisters, but they are afraid lest in struggling for the ballot for themselves they should in some way help the Negro woman.’” Historian Suzanne Lebsock wrote: “There was nothing an African American could say [in Virginia] that would help the woman suffrage cause.” They knew southern legislators were not likely to enfranchise women if it meant black women also could vote. Shortly after the May 1914 suffrage parade in Hampton, the St. Luke Herald’s editor echoed that sentiment writing, that white women ‘”even in Virginia, even in Richmond’ were organizing and that southern politicians would help them ‘were they not afraid that suffrage for women, would include Negro women.’” Consequently, black Virginians had little to no voice in the public discussion. But, they continued to voice their opinions in the black women’s clubs and organizations.

Anti-suffragists played upon racial fears, arguing that giving white and black women the vote would double the total black vote. In Virginia, the news media and anti-suffragists stoked phobias of “Negro Rule.” Realizing the racial issue would threaten their objective, the ESL released a flyer which claimed giving women the vote would not jeopardize white supremacy. Literacy tests and the poll tax would limit black women from voting as it did black men.

Not all ESL members agreed with their organization’s position on restricting black women from voting. In 1913, author Mary Johnston wrote to ESL President Lila Meade Valentine: “I think that as women we should be most prayerfully careful lest, in the future, women—whether coloured women or white women who are merely poor—should be able to say that we had betrayed them from freedom.”

Anti-suffragists also contended that Virginia’s men were the ‘”natural-born leaders, intellectually and physically superior to their female helpmates….’” Suffragists maintained that understanding and capable women were more than able to address issues like education, health reform, and child labor—issues the thought male politicians were ignoring. Virginia suffragists resolutely argued: ‘”Home is not contained within the four walls of an individual home; instead, home is the community.’”

The ESL concentrated on gaining support in the General Assembly for a voting rights amendment to the state constitution. The league’s attempts in 1914 and 1916 failed in the face of conservative politics, racial tensions, and views of women as helpmates. The ESL knew it had to change course. So, it began working (as did other state organizations) for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

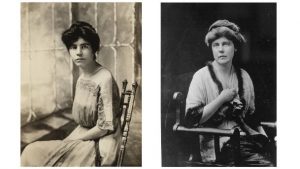

There were other divides in the suffrage movement. Under the leadership of Pauline Adams, Norfolk suffragists were more militant. In 1917, Adams and 12 others were arrested for demonstrating in front of President Woodrow Wilson at a Selective Service parade. The women were jailed at the Occoquan Workhouse in Fairfax County.

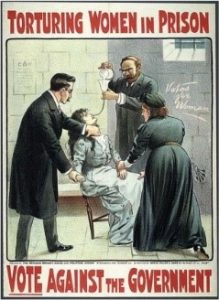

From June to November 1917, a number of nationally well-known suffragists like Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party and vice chairwoman Lucy Burns were arrested from their “Silent Sentinels” pickets of the White House and imprisoned at the Occoquan Workhouse. About 168 women, mainly from the National Women’s Party, were held there. Due to the dirty and appalling conditions, some went on a hunger strike and were force feed. Paul described her force feeding:

“When the forcible feeding was ordered I was taken from my bed, carried to another room, and forced into a chair, bound with sheets and sat upon…by a fat murderess, whose duty it was to keep me still. Then the prison doctor, assisted by two women attendants, placed a rubber tube up my nostrils and pumped liquid food through it into my stomach.”

On November 15, 1917, following orders from the workhouse’s superintendent about 40 guards abused 33 suffragists. Guards struck Lucy Burns and bound her hands to cell bars over her head. She was left in that condition overnight. Affidavits revealed other women were seized, hauled away, hit, strangled, knocked down, squeezed, wrenched, and booted.

No wonder this episode in the suffrage movement is referred to as the “Night of Terror.” It brought national attention to the suffragists and their inhumane treatment, which galvanized sympathy and support for the suffragists. The “Night of Terror” was the Turning Point for woman suffrage.

World War I provided further momentum for the movement. Women’s contributions to the domestic war effort drew attention to their patriotism and to their citizenship capability. Finally, on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified.

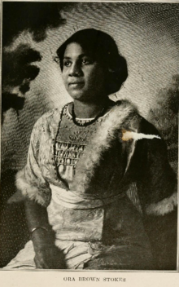

Richmond’s black female leaders like Maggie Walker and Ora Brown Stokes Perry organized voter registration drives and voter education events. Walker, a teacher and the first woman in the U.S. to establish and serve as a bank president, held mass meetings, encouraging black women to vote. They had a month to register before the November 1920 presidential election. But, registrars were unprepared for the large number of women

voters. Three white women were hired to handle white women’s registration while black women had to stand in long lines, waiting to register. Walker went to City Hall, insisting more officials be employed to expedite registration. Social worker Ora Brown Perry unsuccessfully petitioned the registrar of voters to appoint black deputies. In the end, 2, 210 black women registered to vote in Richmond’s 1920 election. They joined thousands of fellow Virginia women in casting their first votes. Thanks to the suffragists one hundred years later women will have the opportunity to vote in the 2020 presidential election.

Sources

For an excellent overview on the subject of Woman Suffrage in Virginia, visit the Encyclopedia Virginia.

Learn more about the National Association of Colored Women from the National Women’s History Museum.

For a profile of Janie P. Barrett, visit the The Library of Virginia’s Working Out Her Destiny Notable Virginia Women.

Learn more about Adella Hunt Logan from Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South, published in 2019 by Yale University Press, and authored by Adele Logan Alexander, Logan’s paternalgranddaughter here.

Read more about Maggie L. Walker from the Maggie L. Walker National Park Service National Historic Site

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR) has a Women’s National History Month Slideshow on the Crenshaw House & The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia

Read about “The Lasting Legacy of Suffragists at the Lorton Women’s Workhouse” in Folklife, a digital magazine from the Smithsonian Center for Folklife & Cultural Heritage.

Learn more about the new book, The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia, published by The History Press and co-authored by Library of Virginia staff members Brent Tarter, Marianne E. Julienne, and Barbara C. Batson, here.

Learn more about African American suffragists from the classic book by Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women In The Struggle For The Vote, 1850-1920, published by Indiana University Press in 1998.