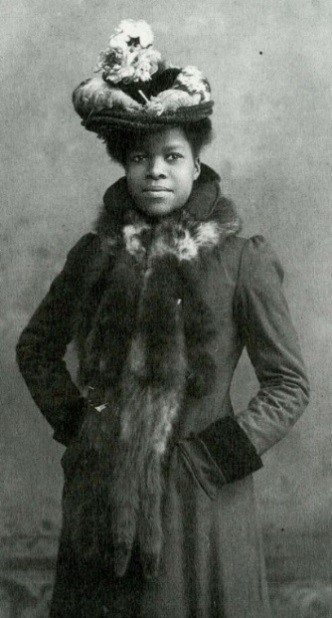

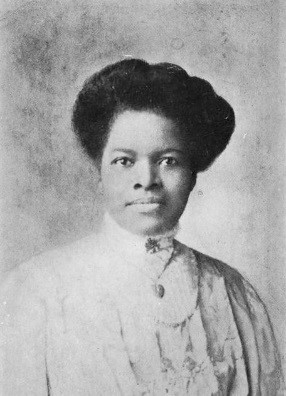

Another trailblazing woman I discovered recently is Nannie Helen Burroughs, an educator, orator, religious leader, civil rights activist, feminist and businesswoman from Orange, Virginia.

Why Remember This Native Virginian?

Burroughs “opened doors in religious and educational institutions, jobs, and society in general, to African-Americans…particularly for women and girls.” Her accomplishments crisscrossed race, religion, gender and age. Burroughs’ works were known across the globe. Nonetheless, she is virtually missing from history—at least for most of us. Burroughs has a lot to teach us from her inspiring vision and achievements–“critical to enhancing the lives of today’s society at large, and particularly our young people.” [The Nannie Helen Burroughs Project (a values and vision initiative), http://nburroughsinfo.org/files/108267653.pdf]

Early Life

Burroughs was born on May 2, 1879. Her father was the son of an enslaved man who had bought his freedom. Her mother was formerly enslaved. After her father died, the five-year-old and her mother moved to Washington, D.C. in search of better educational opportunities. In 1898 Burroughs graduated with honors from M Street Colored High School (now Paul Laurence Dunbar High School). It was among the nation’s first high schools for African Americans. Among her teachers were suffragists and activists Mary Church Terrell and Anna Julia Cooper, who significantly influenced her life.

In the 1890s, Burroughs unsuccessfully applied for a D.C. public school teaching position. Her rejection may have been due to “the prejudice of colorism — a preference for lighter-skinned staff. Put simply, historians say, the Black people doing the hiring believed her to be too Black.” [Jess McHugh, “Denied a teaching job for being ‘too Black,’ she started her own school — and a movement,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/02/28/nannie-helen-burroughs-black-teacher/]

Religious Educator

When Burroughs did not get the job she moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and became associate editor of The Christian Banner, a Baptist newspaper. Burroughs returned to Washington, D.C. and fruitlessly tried to get a civil service position even though she had done well on the exam. In 1900, she accepted a position in Louisville, Kentucky as secretary of the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention (NBC). Founded in 1895, the NBC, USA, Incorporated is the largest African-American organization in the country.

Burroughs organized the Women’s Industrial Club, which offered reasonably priced lunches to area office workers and evening classes in typing, shorthand, bookkeeping, and sewing for its members. The night courses became so popular that Burroughs ultimately hired teachers, releasing her to supervise the program.

“Aspire to be, and all that we are not God will give us credit for trying.” —-Nannie Burroughs

National Acclaim

Burroughs was just twenty-one years old when she earned national renown after delivering a speech, “How the Sisters are Hindered from Helping” at the 1900 National Baptist Convention annual conference in Richmond, Virginia. Below is an excerpt.

We come not to usurp thrones nor to sow discord, but to so organize and systematize the work that each church may help through a Woman’s Missionary Society and not be made poorer thereby….We realize that to allow these gems to lie unpolished longer means a loss to the denomination. For a number of years there has been a righteous discontent, a burning zeal to go forward in his name among the Baptist women of our churches and it will be the dynamic force in the religious campaign at the opening of the 20th century. It will be the spark that shall light the altar fire in the heathen lands….We unfurl our banner upon which is inscribed this motto, “The World for Christ. Woman, Arise, He calleth for Thee.” Will you as a pastor and friend of missions help by not hindering these women when they come among you to speak and to enlist the women of your church? [“How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping,” https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2019/09/26/how-the-sisters-are-hindered-from-helping/]

‘“Who’s that young girl?’ a man in the audience is quoted as saying. Why don’t she sit down? She’s always talking. She’s just an upstart.’ Burroughs had a ready answer for him. ‘I might be an upstart, but I am just starting up.’” [Women’s History Month: Forgotten Foremother Nannie Helen Burroughs, https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2020/3/15/1923809/-Women-s-History-Month-Forgotten-Foremother-Nannie-Helen-Burroughs]

Burroughs might have been called an “upstart” “because she led the organization in the struggle for women’s rights, anti-lynching laws, desegregation, and industrial education for black women and girls. Most people, however, considered her an organizational genius. At the helm of the National Baptist Woman’s Convention for more than six decades, Burroughs remained a tireless and intrepid champion of black pride and women’s rights.” [Burroughs, Nannie Helen, https://oxfordaasc.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.001.0001/acref-9780195301731-e-44056]

She was elected secretary of the National Baptist Women’s Convention, the new auxiliary to the men’s convention. As an inspirational speaker, Burroughs became a dynamic force within the organization. She served as secretary until 1948 whereupon she became president.

At the 1902 Women’s Convention of National Baptists, Burroughs remarked: “The training of Negro women is absolutely necessary not only for their own salvation and the salvation of the race, but because the hour in which we live demands it. If we lose sight of the demands of the hour we blight our hope of progress.”

National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls

Burroughs studied business in 1902 and received an honorary M.A. degree from Kentucky’s Eckstein-Norton University in 1907. After she was denied that D.C. teaching job she later wrote: ‘”An idea was struck out of the suffering of that disappointment — that I would someday have a school here in Washington that school politics had nothing to do with, and that would give all sorts of girls a fair chance….It came to me like a flash of light, and I knew I was to do that thing when the time came.’” [Jess McHugh, “Denied a teaching job for being ‘too Black,’ she started her own school — and a movement,”

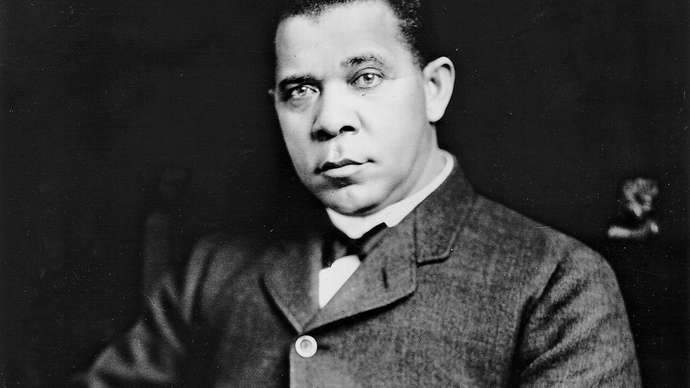

Burroughs recommended her idea for a school to the National Baptist Convention (NBC). After years in the planning phase, the NBC purchased six-acres of land in Northeast Washington, D.C. She obtained money from within the black community, but did not have united support. Virginia native, educator and reformer Booker T. Washington did not think black Washingtonians would donate to the project while others opposed training women beyond domestic work. Burroughs’ motivational speaking helped her raise enough money for the school. Although there were some large donations, most of it came in small amounts from black women and children.

The National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls (later the Nannie Helen Burroughs School) school opened in 1909 with the twenty-six-year-old Burroughs as the first president. It was the country’s first school to offer vocational training for African-American females. She wanted every student to become ‘“the fiber of a sturdy moral, industrious and intellectual woman.’” Burroughs embraced the school’s motto “We specialize in the wholly impossible.” She led the small faculty in teaching students a curriculum on the high school and junior college level. Burroughs thought black women could become “self-sufficient wage earners….” Not only did the school teach domestic arts and secretarial skills, it also offered innovative courses for women like shoe repair, printing, barbering, and gardening. There was an importance placed on grammar and language. Burroughs established the Department of Negro History to impart racial pride in the students. Unlike most of her generation, she thought industrial and classical education went hand in hand. [National Training School for Women and Girls, Trades Hall (Nannie Helen Burroughs School, https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/419]

By the end of its first year, the school had 31 students. Twenty-five years later, over 2,000 women from the U.S., Africa, and the Caribbean Basin attended the school. Burroughs was the principal until her death in 1961. Three years later the institution was renamed the Nannie Burroughs School. In 1991, the school was named a National Historic Landmark.

“Education and justice are democracy’s only life insurance.” Nannie Burroughs

National Association of Wage Earners

Burroughs helped lead the National Association of Wage Earners organized in 1921. The association aimed to systematize and raise living conditions for women, especially migrant workers, and to foster and inspire efficacy in African-American workers. The aim was to uplift domestic service to the level of a science field. Records indicate the association especially focused on ‘”negro women engaged in domestic and personal service occupations in order to provide necessities for their families, and raise their own standard of living.’” Burroughs was president, serving alongside other eminent club women like vice president Mary McLeod Bethune and treasurer Maggie Lena Walker. Their emphasis was more on “public interest educational forums than trade-union activities.” [National Association of Wage Earners,

Self-help and Self-reliance

As a sought-after speaker and writer, Burroughs advanced her belief in “self-help and self-reliance for blacks.” In a July 1927 article for Southern Workman, she urged self-pride: ‘”No race is richer in soul quality and color than the Negro. Some day he will realize it and glorify them. He will popularize black.’”

She was candid in her views about how black men treated black women. She wrote in a 1933 column of a black publication: ‘”Stop making slaves and servants of our women…. The Negro mother is doing it all. The women are carrying the burden. The main reason is that the men lack manhood and energy…. [T]he men ought to get down on their knees to the Negro women. They’ve made possible all we have.’” [https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/burroughs-nannie-helen-c-1878-1961]

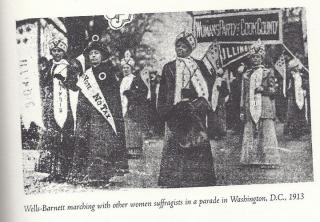

Suffragist

Burroughs championed women’s suffrage. After passage of the 19th Amendment, she worked to register women in 1920. See https://youtu.be/0S5ygVh4VsY; https://youtu.be/bRi4bblFiCU for further information.

Businesswoman

Burroughs was appointed by the administration of Herbert Hoover to chair a committee related to Negro housing for the White House Conference of 1931. She thought cooperatives offered Black communities a sustainable option to the destitutions of the Great Depression. In 1936, she co-founded Cooperative Industries, a “self-help, agricultural and consumer cooperative in Washington DC. As the cooperative’s president, Burroughs used her National Training School as the co-op’s production and manufacturing plant to produce brooms and mattresses. With the help of a grant from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Burroughs expanded the co-op with the purchase of agricultural land in Maryland to form an agricultural producer co-op.” The co-op provided facilities for multiple services, including a medical clinic and variety store. [Looking Back at Women’s History Month, https://www.cdf.coop/post/looking-back-at-women-s-history-month]

In 1933, Burroughs spoke at the Virginia Women’s Missionary Union at Richmond with the address “How White and Colored Women Can Cooperate in Building a Christian Civilization.”

Author and Playwright

In the 1900s, Burroughs wrote Twelve Things The Negro Must Do. It was re-published in 2015 with a commentary by Karen Hunter.

Also see https://blackmeninamerica.com/12-things-the-negro-must-do-to-improve-himself/.

Burroughs was a published playwright. In 1942 she wrote The Slabtown District Convention. She also wrote Where is My Wandering Boy Tonight? Both areone-act plays for church theatrical groups. The Slabtown District was very popular, requiring numerous printings. In fact, in October 2001 Winston-Salem University’s Drama Department “brought the house down with its rendition” of the play. [Slabtown Convention’ brings the house down, News Argus, November 2001, p. 7]

Legacy

At the age of eighty-two, Burroughs died from a stroke in 1961. She “defied societal restrictions placed on her gender and race and her work foreshadowed the main principles of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.”

Library of Congress

The Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. holds the Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers, which span from1900 to 1963. The collection contains 110,000 items; 342 containers plus 19 oversize; 134.4 linear feet; 5 microfilm reels. The types of documents include correspondence, financial records, memoranda, notebooks, speeches and writings, subscription and literature orders, student records, and other papers relating primarily to Burroughs’s founding and management of the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., and to her activities with the Woman’s Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention of the United States of America. For more details check the finding aid at

More information

For more information on Nannie Helen Burroughs whose passion to ‘”beat and ignore until death’ the restrictions society presented to her [which] burned throughout her life” [Forgotten Foremother Nannie Helen Burroughs, https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2020/3/15/1923809/-Women-s-History-Month-Forgotten-Foremother-Nannie-Helen-Burroughs] check out these selected sources:

Kelisha B. Graves, editor, Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of An early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900-1959.

Barbara Sicherman and Carol Hurd Green, eds. Notable American Women: The Modern Period, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980.

Jessie Carney Smith, ed., Notable Black American Women, Detroit, MI: Gale Research, 1992.

F. Ohles, et al, Biographical Dictionary of Modern American Educators

D. S. Salem, African American Women: a Biographical Dictionary

Some Burroughs Quotable Quotes

“To struggle and battle and overcome and absolutely defeat every force designed against us is the only way to achieve.”

“Anything that is as old as racism is in the blood line of the nation. It’s not any superficial thing-that attitude is in the blood and we have to educate about it.”

“At times we feel wounded, hurt, disappointed, disgusted, resentful, sick of it all. At other times we feel skeptical, outraged, robbed, beaten. We chafe, hate, overlook. Then again we feel like ignoring, defying and fighting for every right that belongs to us as human beings.”

“What is your purpose? Why are you here? Start small and find out.”